This essay is a transcript of a presentation given by Naomi Hart highlighting a selection of punk zines in Stuart Hall Library Zine Collection given on 6 May 2022

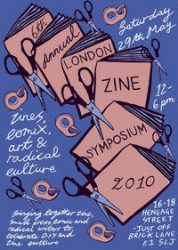

Stuart Hall Library’s contemporary collection features around 400 artist and activist zines which address the subject areas of cultural identity and diversity, visual culture, and platforming underrepresented voices. Zines are DIY self-published magazines, typically with a small circulation, and are affordable or free. Zines are rooted in social histories of protest movements, radical subcultures, and projecting the voices of marginalised communities, and fit well within the library’s collection development policy. While browsing through the zines, which are kept on an open shelf by the entrance to the library, it caught my attention that many of them were about punk music and culture, and the intersections of punk with other themes, such as race and identity, feminism, female readerships, and queer culture.

Punk is a counter-cultural movement that centres on punk music and other forms of creative expression, with an anti-establishment ethos that promotes rebellion, non-conformity and individual freedom. According to the writer Chloe Arnold, “In the ‘70s and ‘80s, the main hub of zine culture became the punk scene in London, LA and New York.” And in the 1990s, the feminist riot grrrl movement emerged as “an alternative to the male-driven punk world of the past”, encouraging women and girls to start bands and make zines themselves (Arnold, 2016). An example of this is Electra, a zine by Jane Collins that focuses on music and women. The third issue, published in 2001, includes an interview with Allison Wolfe, lead singer of the riot grrrl punk band Bratmobile.

It struck me how some of the unique ways that zines are made evoke characteristics of hand-made punk fashion. For example, Bare Fuckeries by Abondance Matanda is bound in recycled red fabric and held together with safety pins. This zine explores Black British identity, mental health, cultural terrorism and language, primarily through poetry. One particularly powerful poem, “Skeng Punks”, is about Mark Duggan, a black British man who was shot and killed by police in Tottenham in 2011 (page titled “SKENG PUNKS”). With skeng meaning weapon or hyped (‘skeng’, 2021), the poem incentivises people to be “skeng Punks” and organise “strategies” to actively make change.

Music journalist and Goldblade singer, John Robb once quoted about Poly Styrene, lead singer of punk rock band X-Ray Spex, that “The great thing about punk was that it tore the fabric a bit, and when any kind of cultural things are formed, you can make the rules up as you go along” (Belle and Howe, p.95).

The great thing about punk was that it tore the fabric a bit, and when any kind of cultural things are formed, you can make the rules up as you go along” (Belle and Howe, p.95).

So, with that in mind, I’m going to highlight some of the punk zines in Stuart Hall Library and how the zinesters (creators of zines) describe their material.

Six issues of Shotgun Seamstress are held in a collected volume at Stuart Hall Library. In Shotgun Seamstress, Osa Atoe explores their own identity and the marginalisation of black punks within the punk community. In the first issue they write this: “I think that in predominantly white movements, including the punk scene and activist circles, there are lots of judgments and assumptions about black people and a total lack of understanding about what real black people (and specifically black women), have to do to make it through the day” (p.15). I noticed the development of the zine’s tag line between its first and final issues, changing from “A zine by and for black punks” (p.10) to “Shotgun Seamstress is a zine by, for and about Black punks, queers, feminists, artists, musicians & activists” (p.190), which may indicate the zinester was trying to clarify and expand audience inclusivity.

Zines express a wide range of reflections on identity. For example, Different times is a memoir of Simon Murphy’s time in the punk-drag band Six Inch Killaz, comprised of 5 drag queens. The zine describes the clubs they went to (such as The Way Out) and the wider drag and queer scenes in London, and is filled with stylish black and white illustrations that enhance the storytelling. Simon, whose drag name was Mona Compleine (pronounced “complainer” (p.16)) says this: “I did drag from 1992 to 2001, and most of that time I was in a band, an all-drag punk-ish band: Six Inch Killaz. This zine is mostly about me and the band, but it’s also about the drag, trans, queer and music scenes in London that we were part of” (p.3).

Many punk zines in Stuart Hall Library are grounded by a feminist perspective. Adventures Close to Home is a fanzine about The Slits, a female punk band that formed in London in 1976. According to Steiner, The Slits were the “OG” “punk, post-punk, girl punk, dub-punk, urbanferal indie riot punk” band (p.2). I admire how this zine shines a light on the gender biases in the world of punk rock music reviewing, which privileges male groups above women’s contributions to the movement. Steiner writes that “The Slits have a bad rep with malestream publications who either ignore/d them all together, or use them as backdrops to bands like The Clash and the Sex Pistols, or focus on describing how they looked and how bad they sounded” (p.2). Steiner highlights particular reviews for evidence. By contrast, she celebrates The Slits’s sound which “intentionally defies categorization” (p.4), in comparison with male punk rock bands that, in her opinion, became facsimiles of each other.

By nature, zines are experimental. Published in Japan, Playback Lady Zine is creatively structured like a vinyl record around eleven female punk and post-punk songs that have been selected by Constance Legeay and Aya Miyake. The writers share their personal relationships to the songs, nostalgic memories of first hearing them, and think about punk more widely. For example, Aya meditates that “Many punk songs have been sung in protest against prejudice towards sexualities and untold gender roles” (“Breaking the Rules / Ludus” page). The zine comes with a mix CD to listen to while reading. I’ve added these songs to the playlist accompanying this project.

The Hissterics is edited by Rachael House, but includes contributions from other creatives. The zine pays homage to a fictional 1970s/80s feminist punk band called ‘The Hissterics’ and acts as an imagined archival effort to recover their lost, albeit mythologised, history. Rachael House calls out to her audience for information about their story: “So – I’m appealing to you. Have you got any information to share with me?” (p.5). Contributors to the zine add to this archival recovery effort through writing about memories of the band and memorabilia. I like how this creative zine speaks to lost histories of female music groups and criticises the red tape that can limit access to archives.

Punker Pages addresses accessibility to punk from a different angle, by being a directory for zinesters and other promoters who “contribute something to the punk scene” (p.3). Designed by the zinester Chris X, it’s essentially the Yellow Pages for all things punk, from music to reading. Something I like about this zine is how it reaches out to its audience by repeatedly welcoming feedback. The message is: “Basically just talk to me, I don’t bite and I’m pretty dependent on your input” (p.3). Many of the zines discussed here ask for audiences to get in touch and share feedback.

Reading a zine is an active process that connects readers and zinesters. Whether you’re a novice or experienced zine reader, I would recommend browsing through the brilliant collection at Stuart Hall Library. Punk culture is just one theme in a wealth of subjects to explore. Thank you for listening.

Watch the presentation

Playlist

- Oh Bondage! Up Yours! – X-Ray Spex

- Trashola – Six Inch Killaz

- I Wanna Make a Fanzine – Irreparables

- The Didn’t Song – Dolly Mixture

- Her Story – The Flying Lizzards

- You Go to My Head – Lio

- That’s the Way Boys Are – Y PANTS

- It’s a Shame – Monie Love

- Breaking the Rules – Ludos

- Psynomey – Masako-san

- Vivian – OXZ

- Wuthering Heights – Kate Bush

- #&* – Mary Ocher + Your Government

- Cool Schmool – Bratmobile

Bibliography

Arnold, Chloe. (2016). ‘A Brief History of Zines’. Available at: https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/88911/brief-history-zines. (Accessed: 29 April 2022).

Atoe, Osa. Shotgun Seamstress: zine collection. (2012). Tacoma, Washington: Mend my dress press. Shelfmark: ZIN ANT ATO.

Get in touch: shotgunseamstress@gmail.com ; www.issuu.com/shotgunseamstress.

Bell, Celeste and Howe, Zoë. [2019]. Dayglo. London: Omnibus Press.

Collins, Jane. Electra. Shelfmark: ZIN ELE.

Get in touch: Electrazine@hotmail.com.

House, Rachael et al. (2011). The Hissterics. [United Kingdom]: www.rachaelhouse.com. Shelfmark: ZIN HIS.

Get in touch: rachaelhouse@me.com.

Legeay, Constance and Miyake, Aya. (2017). Playback Lady Zine. Shelfmark: ZIN PLA.

Get in touch: http://rosavertov.net/ ; http://miyakeaya.tumblr.com/.

Motana, Abondance. (2016). Bare Fuckeries. Shelfmark: ZIN BAR.

Get in touch: @abondance ; #barefucker1es ; abondance.bigcartel.com.

Murphy, Simon. (2013). Different times : drag, life, rock ‘n’ roll: five years in Six Inch Killaz, 1994-99. United Kingdom: footprinters.co.uk. Shelfmark: ZIN DIF.

Get in touch: compleine@yahoo.com.

‘skeng’. (2021). Available at: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/skeng#:~:text=skeng%20(plural%20skengs),or%20a%20knife%20quotations%20%E2%96%BC. (Accessed: 5 May 2022).

Steiner, Melissa. Adventures Close to Home. A Zine About The Slits. Shelfmark: ZIN ADV.

Get in touch: Melissa@; m_steiner_@hotmail.com.

X, Chris. (2010). Punker Pages. United Kingdom: footprinters.co.uk. Shelfmark: ZIN PUN.

Get in touch: punkerpages@gmail.com ; www.punkerpages.com.

Recommended Further Reading

Moran, Stephanie. (2018). ‘Developing the Stuart Hall Library Zines Collection at Iniva’. Art Libraries Journal, 43(2), pp.88-93.

iniva. ‘About the Collections’. Available at: https://iniva.org/library/library-and-archive-collection/. (Accessed: 4 May 2022).