Cheraine Donalea Scott, Stuart Hall Library volunteer, explores her interest in contemporary Britain through grime music using Stuart Hall Library collections.

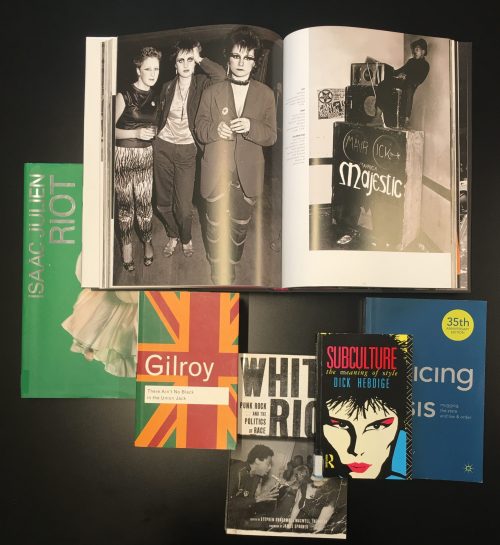

Image of Isaac Julien’s Riot, White Riot: Punk Rock and the Politics of Race, Syd Shelton : rock against racism

Despite what may seem like a politically unprecedented and polarizing contemporary moment, there are many political and cultural parallels to be made with 1970’s Britain. Both blighted by analogous episodes of economic recession, problematic immigration policies, heightened racism and the rise of far-right populist movements. These moments of political crises have also induced counter-cultural responses, evident in the 1970’s punk movement and grime music today. This phenomena where counterculture, media, and politics combine to challenge the dominate national narrative in a dynamic way is often sidelined from the main political analysis and its ideological potency underestimated.

This aligns with the research I am currently working on, which explores the potentially of grime music as a transformative politics that challenges notions of national identity, through its interracial class relations. The punk scene of the 1970’s can also be read as conveying a similar cultural politics. While it was not my immediate intention to explore the historical parallels between the two British music cultures, navigating the library, in my role as volunteer, allowed me to be more open to the material I encountered and lead me the oversized book Syd Shelton: Rock Against Racism, which became integral to the way I approached my research in the library. Amending search keywords to ‘punk’, ‘riots’ and ‘1970, Britain’, the year 1976 began to stand out as a significant historical year with many discernible parallels with the present-day.

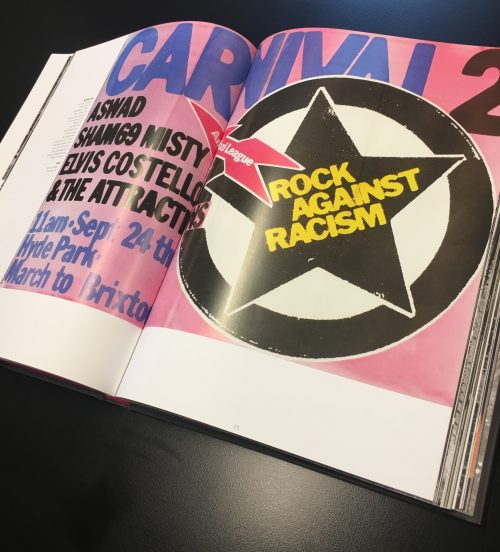

Street Poster, Carnival 2 in Syd Shelton : Rock Against Racism.

In the book Syd Shelton: Rock Against Racism a stunning array of Shelton’s photography is juxtaposed with essays and interviews that explore his work with Rock Against Racism (RAR). Founded in 1976 by Shelton and ‘a small group of activists in or around the Socialist Workers Party,’ RAR was launched as a direct challenge to the expressed support of fascism by British musicians Eric Clapton and David Bowie (Gilroy, 1992: pp.120). Marshaling together the rebel sounds ‘of reggae and punk and the fantastic creative explosions happening at the same time,’ RAR resisted popular racist sentiments through a cultural campaign rooted in a love for music (Autograph ABP, 2015: pp.17). Famed for their star insignia, which was often worn in badge form by its members, RAR launched the magazine Temporary Hoarding, in 1977. The fanzine covered music and social news as well as essays that demystified complex notions such as racism and labour capitalism. Additionally, in 1978, together with the Anti-Nazi League, RAR put on multiple music concerts up and down the country which brought together tens of thousands of people, with performances by acts such as The Clash, Aswad and Elvis Costello.

Cover of Temporary Hoarding No. 10, 1979 in Syd Shelton : rock against racism with other books

Writing about the 1970’s punk scene, Dick Hebdige, recalls the summer of 1976 as ‘extraordinarily hot and dry’ (Hebdige, 1976: pp.24), noting further that:

In late August… the Notting Hill Carnival, traditionally a paradigm of racial harmony, exploded into violence… It was during this strange apocalyptic summer that punk made its sensational debut in the music press. (Hebdige, 1976: pp.24-25)

With caution not to read these events as serendipitous, Hebdige reveals the year as both ushering in the explosion of punk music into the mainstream and witnessing the Notting Hill riots. Despite being in its 11th year, in 1976, growing political opposition by local council and white tenants lead to multiple attempts to undermine the Carnival and resulted in its over policing (Race Today, Sept 1976). According to Punk music journalist, Jon Savage, in 1976 ‘the police changed their tactics, increasing their presence from just under 200 the previous year to nearly 1,600’ (Duncombe & Tremblay, 2011: pp.161). By preparing for a confrontation they had not experienced in previous years, the overzealous presences of the Metropolitan Police at the 1976 Carnival epitomizes the systematic and institutional racism experienced by Black communities in Britain.

Issac Juliens Riot. Chapter 1, Fire

For further context, the actions of the Metropolitan Police at the 1976 Notting Hill Carnival existed in a decade gripped by a “mugging” moral panic. A crime with little to no legal distinction from theft, the moral panic around muggings were fabricated by the British news media who saturated the nation with images of young Black muggers and perpetuated by the Met Police and British judicial system (Hall, 2013). The egregious response by the British justice system towards the mugging panic eerily echo the actions taken during and in the aftermath of the 2011 UK Summer Riots. Often depicted as riots without a cause, the issue of policing and race relations was at the heart of the 2011 UK Summer Riots. Starting in the working-class and racially diverse urban area of Tottenham, North London, the riots occurred after Mark Duggan, a Tottenham local, was gunned down by a covert specialist police unit. Over the course of six days, working-class youth in urban areas across the UK took to the streets to protest police harassment in their communities.

Militant Entertainment Tour, West Runton Pavilion, Cromer, Norfolk 1979 in Syd Shelton : Rock Against Racism.

The same generation of frustrated young people who took to the streets, during the 2011 riots, intersects with the politically astute ‘Generation Grime’ that sociologist Monique Charles identifies (Soundings, Spring 2018: 68: pp.40). A generation of young working-class people, up and down the country, who are economic and socially disenfranchised due to the recent recession and austerity policies. Comparably, Savage reflections on 1976 as a year ‘under economic attack’ and says that ‘the “social contract” was beset from all sides by a multitude of conspiracies against the English way of life’ (Duncombe & Tremblay, 2011: pp. 157). Which identifies the experiences of young people in Britain, in the 1970’s, particularly those involved in the punk scene, as motivated by a similar sense of social and economic alienation. Also, the 1976 Notting Hill Riots played an important role in the ideological formation of punk music with members of punk band The Clash said to have been present at the Carnival the year it descended into a riot. Speaking on the encounter, Joe Strummer is noted saying that:

I realized I had to write a song called ‘White Riot’ because it wasn’t our fight. It was the one day of the year when the blacks were going to get their own back against the really atrocious way that the police behaved. (Duncombe & Tremblay, 2011: pp.161)

According to scholarship on punk music, ‘White Riot’:

…was a call to arms for White punks… to build alliances with Blacks and other oppressed minorities, who had something to teach young Whites about rising up and resisting the powers-that-be. (Duncombe & Tremblay, 2011: pp.154)

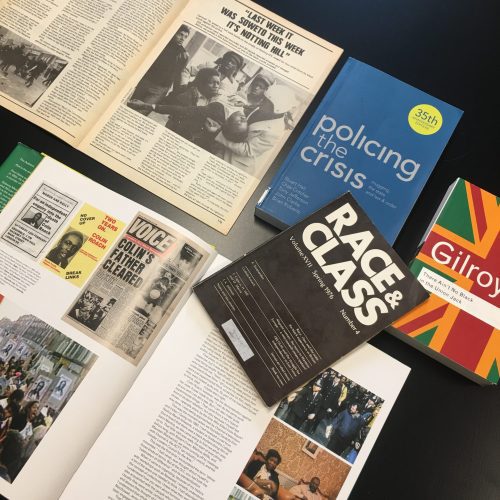

Image of Race and Class, There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack, Policing the Crisis

In both instances of riots, music played an important role in fostering interracial class kinships and social consciousness. Syd Shelton touches on this, saying that working-class “black and white youth… [had] a vision for a better way of living in this country and that we could actually change some things“ (Autograph ABP, 2015: pp.20). While it may not seem so, this is a powerful political stance for young Black and white British youth to take. As according to prominent race scholars who were writing at the time, the function of British racism was attributed to the active separation of ‘a black under-class from bringing’ its ‘peculiar political dimensions’ to the white workers own historical struggles against capitalism (Sivanandan, Race & Class: 1976: 17: pp.347). Phrased another way, despite class oppression experienced differently depending on race, the working class shares a common interest in challenging the state, that acts as the arbiter for capitalism and requires a constant source of cheap labour, which maintains the British class system.

A similar political reading can be attributed to grime music which operates as a multiracial space where black, white and Asian youth contribute as both producers and participants. However, an important distinction to be made between the two genres is that grime is a black music style rooted in a black British sound culture. Whereas punk music was, as Hebdige appropriately acknowledges, ‘emphatically white’ (Duncombe & Tremblay, 2011: pp.40). Though, the influence and intimate connections between reggae music and punk is well documented. The rebel sound of Jamaican reggae music, which expressed ‘the burden of the history’ of black oppression and resistance (Johnson, Race & Class: 1976: 17: pp.398), ‘attracted those punks who wished to give tangible form to their alienation’ (Duncombe & Tremblay, 2011: pp.38). So much so that Hebdige describes the punk aesthetic as capable of being read ‘in part as a white “translation” of black “ethnicity”’ (Duncombe & Tremblay, 2011: pp.39).

Recognizing the racial distinctions between the two genres is necessary since it offers a glimpse into the ways racial meaning and interracial class relations play out in everyday British life. This, contrasted with a reading of the dominant political regime playing out concurrently can provide an understanding (and possibly foresight) of the engineered social shifts these moments of crises tend to usher in.

Biography

Cheraine Donalea Scott is currently completing a PhD in Media, Culture and Communications at the New York University. Her research explores the political intentions of UK Grime music in the current UK political climate, looking at the music’s impact on black and white working-class urban youth.

Bibliography / Recommended Reading

- Syd Shelton: Rock Against Racism, Autograph ABP (London: 2015)

- A Riot of Our Own, Carol Tulloch, Chelsea Space, July 2- August 2, 2008 [exhibition booklet]

- White Riot: Punk Rock and the Politics of Race, Ed. Stephen Duncombe & Maxwell Tremblay, Verso (London: 2011)

- Riot, Isaac Julien, The Museum of Modern Art (New York: 2013)

- Race Today,September 1976 [Carnival coverage]

- ‘Race, Class and the State: The Black Experience in Britain’, A. Sivanandan, Race & Class(1976; 17), pp. 347-368

- ‘Jamaican Rebel Music’, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Race & Class(1976; 17), pp. 397-412

- ‘The Jamaica 1970s and its Influence on the Making of Black Britain’, Eddie Chambers, Small Axe (2019; 58: 23: 1), pp.134-149

- There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack,Paul Gilroy, Routledge (London: 1992)

- Subculture: The Meaning of Style, Dick Hebdige

- Policing the Crisis (35th Anniversary Edition), Stuart Hall, Chas Critcher, Tony Jefferson, John Clarke, Brian Roberts, Palgrave Macmillan (London: 2013)

- ‘Music, politics and identity: from Cool Britannia to Grime4Corbyn’, Rhiannon E. Jones, Soundings (Winter 2017-18: 67), pp. 50-61

- ‘Grime Labour’, Monique Charles, Soundings (Spring 2018: 68), pp.40-52