Stephen Weller, Stuart Hall Library volunteer explores his interest in New Media and Net Art (Internet Art) and artists in the Stuart Hall Library collection.

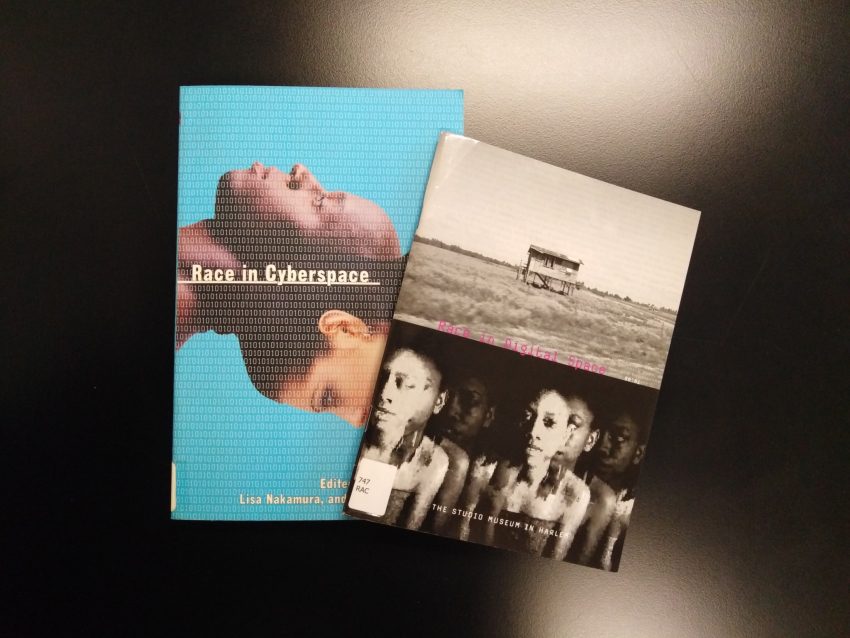

Early conceptions of the Internet hinged upon utopian ideals of shedding the confines and complications of race and gender – going online would mean leaving the body, and the social categories attached to it, behind. However, as Beth Kolko, Lisa Nakamura, and Gilbert Rodman assert in Race and Cyberspace (2000), ‘neither the invisibility nor the mutability of online identity make it possible for you to escape your “real world” identity completely.’

I wanted to use my time at Stuart Hall Library to better understand art produced at the turn of the century from artists of colour in the emerging fields of new media and net art and how it dealt with the uncertainty of online space.

Many of these artists were interested in the potential of new technologies, but also recognised their replication and reintegration of the hegemonies of race and gender. Despite the ways in which the Internet has evolved over the past 20 years, how its spaces have become more surveilled and policed, more narrow and yet simultaneously more networked and far-reaching, artists continue to explore these ambiguous opportunities.

Race in Digital Space

In looking for these connections in Stuart Hall Library, I came across the exhibition guide for Race in Digital Space, published alongside the exhibition’s showing at The Studio Museum in Harlem in 2002. In curator Erika Dalya Muhammad’s own words, the exhibition sought to ‘contextualize race as a dynamic power system’ and uncover politically potent work in order to ‘comment on digital culture, to chronicle history, and to anticipate future realities.’

The artists featured in the exhibition that I was most drawn to did feel almost anticipatory in their recognition of an embodied perspective to identity conception and construction online. Their works emphasise the problems and power relations that remain inherent in choosing to represent visually in digital space, and, in doing so, establish clear parallels to a number of current artistic practices.

Future Realities

Included in Race in Digital Space, Prema Murthy’s Bindi Girl is an interactive web-based performance piece evoking early-Internet era chat rooms and cam shows, in which Murthy’s avatar ‘Bindi’ is shown in a cycling series of pornographic photos, the nudity of which is deliberately obscured by red bindi. Murty draws parallels between technology and religion, questioning them as a means of liberation, referring to Bindi as ‘the embodiment of the “goddess/whore” archetype that has historically been used to simplify the identity of women and their roles of power in society.’

Like Bindi Girl, two more recent artworks, E. Jane’s E. The Avatar (2015) and Sondra Perry’s Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation (2016), present digital representations of the artists’ image as a means to investigate how race and gender play out in online culture as a supposedly utopian, disembodied space.

- Jane’s YouTube-based performance piece E. The Avatar features the artist addressing the viewer directly in an emotionless and sarcasm-laden deadpan. Romanticizing her existence as a web presence, E. suggests that the viewer themselves should become more digital and embrace the hybrid potential of online technologies.

- The Avatar is accompanied by custom clothing items featuring E.’s face and body printed across the material, mirroring Murthy’s sale of souvenirs on the Bindi Girl webpage (socks, bindi dots, panties, and goddess prints). E. Jane’s work considers the plurality of identity available online: shareable, purchasable, commodified by the logic of digital capitalism.

Sondra Perry’s Graft and Ash… displays a self-portrait of Perry-as-avatar in disembodied form, an animated head suspended in a virtual, ambiguous space. A text-to-speech translation explains that Perry ‘could not replicate her fatness in the software that was used to make us’; her body type was not a pre-existing template.

Throughout the piece, Perry’s avatar remarks on several equally pointed, but also deliberately ambivalent, qualities of their representation through technology. Perry’s avatar concludes, ‘just being who we are is extremely risky. We are a DIY. Not all that a representative thing, which makes being a being impossible – or whatever.’

The considerations that inform these works reveal the continued awkwardness of the Internet as a domain for the construction of identity. These artists ask what might be left out of cyber representation and the abandonment of the body and what sticks or is multiplied when technological presentations of identity are allowed to shift and morph.

Other works within the exhibition also explore the ways in which race and the body are mediated online, circulated through digital spaces. In their piece, my hands/wishful thinking, Keith & Mendi Obadike construct an Internet memorial for Amadou Diallo, who was killed by New York policeman in 1999. The policeman involved claimed that they thought Diallo’s wallet was a gun.

The Obadikes considered how much of the information they received about Diallo’s death was delivered through the Internet, deciding it was fitting to mourn him in digital space. The webpage for the work features a repeated image of Keith Obadike’s hand, clutching a wallet purchased from the store at which Diallo worked. The page is punctuated by 41 ‘thoughts’, one to counteract each bullet fired and, in Mendi Obadike’s words, ‘reject the negative forces directed against us, the survivors.’

In 2013, Devin Kenny created Untitled/Clefa which, though not an online work, was woven through with similar considerations of networked culture and its relationship to anti-black violence. The performance piece, staged only once, is a re-enactment of ‘Trayvon-ing’ – a meme circulating on Tumblr and elsewhere shortly after the killing of Trayvon Martin in 2012.

In the meme, predominantly white teenagers lay face down on the ground in an arrangement mocking the details of Martin’s death: wearing a hoodie, with Skittles and Arizona iced tea. Kenny’s physical embodiment of this meme, the implication of his own body in its iconography, serves as an intense moment of identification with Martin and reinscribes a sense of materiality and presence in much the same way as Keith Obadike’s hand and wallet do in my hands.

Another work from E. Jane, Alive (Not Yet Dead) (2016), echoes the Obadikes’ efforts to resist feelings of apathy in its response to the death of Sandra Bland in 2015. E. Jane created a pastel coloured webcam background with the word ALIVE fixed to the top and took photos in front of it to be shared on social media, asking other Black women to do the same.

As much of the specifics of Diallo’s death had been ‘filtered through the lens of the browser’, so too had those of Martin and Bland. The women involved in Alive (Not Yet Dead) and Devin Kenny himself are purposefully entangled in the circulation of images of racial and gendered violence shared by a largely white audience. These works stand in mourning as a collective announcement and enactment of survival in a sea of spectacle and consumption. Their use of networked space shapes it as site of collectivity, visibility, and selfhood, an acknowledgement of humanity and hope in moments of distress and death.

Throughlines

It has been exciting to discuss some of the works within Race in Digital Space and their significant parallels to more recent artistic practices dealing with questions of technology and the body – especially within the context of the Stuart Hall Library and Iniva more generally. Iniva’s support and commission of dynamic and interactive projects was central to early creative discussions probing and broadening these junctures. Works like Keith Piper’s Relocating the Remains, Donald Rodney’s AUTOICON, and Joy Gregory’s Blonde (produced as part of Iniva’s x-space programme and virtual gallery), among others, highlighted the critical properties of the Internet as an artistic medium as well as the uneasy conditions of digital representation.

Participation in networked space does not equal freedom from the racialized and gendered confines of the body. The body, holding and using memory and experience as the interface through which we come to understand the world and our own identities, still underwrites the possibilities of technology and experiences online. The development of the Internet – alongside the biases of machine-learning, facial recognition software, and the constant surveillance and ordering of big data – has only served to exacerbate this relationship.

However, by reclaiming and foregrounding embodiment within their works, these artists, in acts of technological appropriation, demonstrate a flexible resistance to systems of control. Just because the boundary lines are drawn much clearer and feel more restrictive now than at the Internet’s inception, do they have to remain so? What space might there be for new forms of subjectivity online which refuse to take the disembodied figure as their starting point?

Biography

Stephen Weller is an Art History graduate living in London. His interests include playing video games, making digital art, and dance music. He hopes to pursue a PhD exploring the intersections of identity, technology, and online visual cultures.