Lyn French (A Space Director) explores the theme of time passing, and our relationship to it, in this blog. Examples given feature images from our new set of Emotional Learning Cards ‘How do we live well with others?’

*NEW * Creative Learning Packs are now being made available featuring key themes from our blogs. Each pack includes worksheets, art tasks and related ‘Word Banks’. The first in this series is entitled ‘Reflections on Endings’ and is designed to be used in group or individual therapy sessions across all ages or in PSHE lessons. The exercises can be printed and used as they are or adapted to suit a specific context. The pack costs £5 and can be paid for + downloaded in our store.

In everyday life, time marks out the minutes, hours and days of our week. Maybe we imagine time is on our side and we have the luxury of going at our own pace without being under pressure to rush. In other instances, time can feel persecuting, as if it’s going to run out before we can accomplish what we set out to do. We learn about time in our earliest months when, as infants, a delay in our needs being met brings into being a ‘felt awareness’ or an ‘embodied knowledge’ of a time lag between desire and its fulfilment. In some instances, our infantile frustration at having to wait will have been tinged with a primal dread that our cries might go unnoticed, threatening our very survival. No mother can be ever-present for her baby nor would it be helpful – we need to become aware that there is an ‘other’ who is separate from us and on whom we are dependent so that the scene is set for learning to relate to those around us. The absent mother, when experienced in manageable ‘doses’, lays the foundation for developing a concept of time and an awareness of separateness. The need to develop a repertoire of sounds and signals in order to communicate is stirred and the first sign of ‘language’ begins to evolve. Studies show that babies do not simply communicate hunger or the need to be changed but express a wish to relate to, and engage with, the mother in part to generate a feeling of connectedness to counteract the ‘alone-ness’ that comes with feeling separate.

In later years, our relationship to time is influenced by the interplay between factors rooted in the ‘here and now’ and our emotional geography. The latter comprises the layers of experience we have amassed, each conscious or unconscious ‘memory’ embedded with emotionally charged psychic material dating from infanthood onwards. For those who have enjoyed ‘good enough’ early experiences of feeding, weaning, separation and loss, waiting for gratification or for ‘time to tell’ is not so intolerable. At the other end of the spectrum are those for whom the reality of frustration, ratcheted up by the unconscious fear of being left abandoned with needs unmet, came too soon and too frequently, leaving a reservoir of terror often hidden under a thin crust of anger.

Bani Abidi ‘Intercommunication Devices’ 2008

Calling out in the dark when there is no corresponding reply brings to mind Bani Abidi’s photograph entitled Intercommunication Devices, 2008 (see above). Speaking into an intercom, anticipating a response but receiving none, can be disappointing or worse, echoing one’s earliest experiences of searching for a connection.

Sonia Boyce ‘She aint holding them up, she’s holdin on’ 1984/1986

Implicit in our concept of time is the unavoidable fact that all which begins also ends. In common with the woman in Sonia Boyce’s pastel and ink drawing Big Women’s Talk / She aint holding them up, she’s holdin on (some English Rose) 1984/86 (see above), we all carry memories of times past, especially those rooted in family, and we re-shape these memories as the years advance. Maybe the end of childhood, for instance, is now seen as marked primarily by losses rather than gains. Gone are the moments of carefree play and excited exploration, replaced by long school days defined by learning, sitting tests and encountering social challenges with peers. Or perhaps childhood’s end brings the pleasure derived from increased independence and the chance to try to shape our own destiny. For some, moving on from childhood into adolescence is a welcome relief as distance can be placed between oneself and other members of the family which may be the only way painful, conflicted or confusing relationships can be managed or even survived. Many of us may have been called upon to provide emotional support for vulnerable parents, propping them up, or have simply ‘held on’ until such time as we can leave home and carve out our own lives. Our perceptions of childhood, and what the transition into adolescence signifies, will be coloured by how we remember the past which, in turn will to some extent, determine what we project into the future.

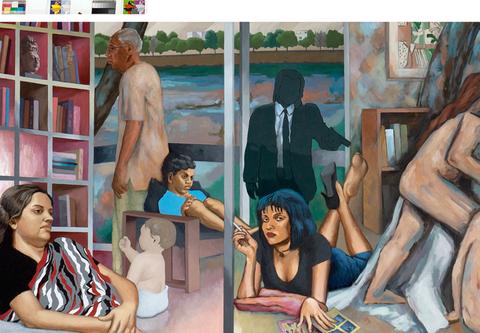

None of us can shed our past but it does not have to hold us in its grip. We can look back on it and gain an understanding of the bigger picture. Sudhir Patwardhan’s image Family Fiction, 2010 (see above) reminds us that we all create stories about our family members and our relationships. For example, if our father left when we were young and has not maintained contact, we might explain this by convincing ourselves that we are of little interest or value and even ‘unloveable’. This story can harden into a core belief either consciously or unconsciously and colour the image we project of ourselves throughout the remainder of our lives. Alternatively, we can try to figure out why a father might leave and never return. Perhaps the guilt he feels about not being able to sustain a healthy relationship with our mother is too great to be borne. Or he might have been abandoned himself in early years and simply not know how to be a father. Perhaps he is compelled to ‘keep moving’ to hold at bay unconscious fears and anxieties. Whatever the psychological context, which we may never uncover, there will always be an emotional subtext. No one sets out to be an absent father but is usually driven into this position by unconscious forces which will have a powerful emotional content. If we place ourselves centre stage in the stories we create about our family relationships, we may risk living out a life built on a very disempowering self-image based purely on speculation and ‘fictionalised’ stories we tell ourselves.

Sudhir Patwardhan ‘Family Fiction’ 2010

To further complicate matters, many of us idealise what we feel we’ve missed out on. If, for example, we haven’t had a father available to us, or if we had adoptive or foster parents, we might hold onto a rose-tinted picture of what being a member of a ‘real’ family might be like. Perhaps we imagine the relationship between a birth parent and a child being one defined by intuitive attunement and mutual love as Shirin Neshat’s photograph Bonding, 1995 (see above) seems to depict. However, Neshat’s image captures a moment in time, not a continuous ‘flow’. If we romanticise what we haven’t experienced ourselves, we may end up looking for the ideal relationship later in life to compensate for what we feel we’ve lacked. This can lead to unrealistic expectations, inevitable disappointment and a perpetual feeling that we have been left behind. All of us have to work through the ending of childhood illusions. Life isn’t as smooth or as seamless as our fantasies might have us believe or as some advertising images or accounts of celebrities’ lives might construct.

Shirin Neshat ‘Bonding’ 1995

We can idealise times of the year as well as relationships. As the summer months draw nearer, we are reminded of how holidays conjure up seductive images of endless sunny days symbolising freedom, pleasure-seeking and relief from work. We all carry memories of the end of the school year and remember the excitement it stirs up. However, what can be forgotten are the goodbyes we’ve said to favourite teachers, the loss of daily structures and the fractious moments that can arise between siblings or friends when boredom inevitably sets in. Summer may bring relief from the cold of winter and the wet days of spring but the ‘emotional weather’ continues regardless of where we are and how we are spending our holidays. ‘ Most of us yearn for the ‘perfect family vacation’, forgetting that relationships still feature ups and downs no matter how idyllic the setting or the weather! Mixed conditions’ are bound to be the order of the day.

Order our new pack of worksheets and related resources entitled ‘Reflections on Endings’ to support working through endings in therapy sessions or in the classroom as we approach the end of the academic year.

The images referenced above are part of our new set of Emotional Learning Cards ‘How do we live well with others?’ now available for worldwide delivery in our store. Join one of our workshops on either Thursday 12th June 6-7.30 pm or Saturday 21st June 1.30-3 pm at Iniva to learn about different approaches to using our Emotional Learning Cards. See more information here and book via Eventbrite.