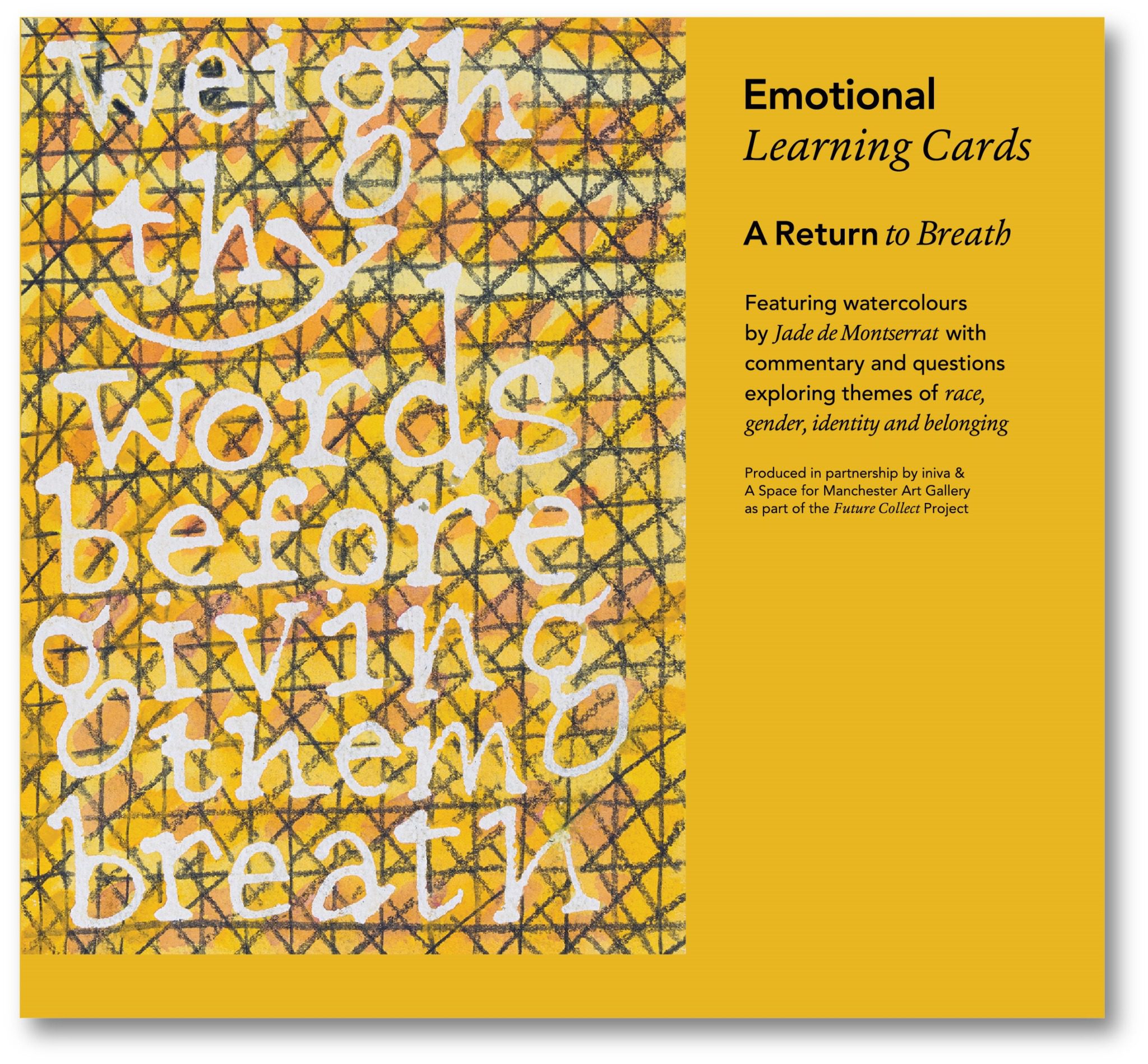

Return to Breath

Photograph: Jade de Montserrat

Image Layout: Sonja Frick

Introducing two new resources: A Return to Breath featuring a watercolour series by Jade de Montserrat and Making that remembers…. a correspondence between emotion and materials based on artworks and works in progress by Maria Amidu.

Understanding ourselves and making better sense of our similarities and differences is dependent on the capacity to be freely and openly curious. Wondering about and puzzling over who we are, how we are seen, and what it means to belong – or the opposite – is commonly associated with the often-tumultuous adolescent years. However, throughout life, thoughts about who we’ve been and who we are in the process of becoming continue to ebb and flow in and out of consciousness, washing up impressions, memories, and fragments of history both personal and collective, each influencing the other ‘in the perpetual back and forth’ to borrow the title of Maria Amidu’s 2024 Towner Eastbourne exhibition. In the academic arena, themes relating to individual, group, social, cultural, and global identities feed into multiple streams of thought running through and between the arts, philosophy, psychotherapy, cultural studies, critical theory, post-colonial studies and so on. Curiosity of this kind is vital for us all to cultivate yet finding the language to put our lived experience into words can prove challenging.

Making the remembers…

Photograph: Maria Amidu

Image Layout: Sonja Frick

The emotional learning cards co-published by iniva and A Space are designed to bridge this gap by providing a starting point for one-to-one and group enquiry.

Using contemporary art and related commentary as a springboard for reflection enables interpretations to be more easily made, back and forth between the ‘here and now’, and the ‘then and there’, crisscrossing individual, social and political spheres. The questions included on each card can be taken in different directions, either opening up general exploration or moving into personal associations. Looking at art without the aim of second guessing the artist’s intentions but instead simultaneously finding/creating meaning for ourselves offers more than the opportunity to build the skills required to read visual languages or to decode the world around us. Inevitably aspects of who we are as individuals and groups are revealed which otherwise might remain hidden from view.

A Return to Breath and Making that remembers… a correspondence between emotion and materials continue this tradition. These sets of emotional learning cards were created in the context of Future Collect, a dynamic three-year programme led by iniva, designed to transform the culture of commissioning and collecting within galleries and museums to reflect the diversity of Britain. Each project in the programme partnered iniva with a national/regional museum or gallery to commission an artist of African or Asian descent, British-born or based. These commissions gave the selected artists an opportunity to develop their practice and to be collected and exhibited by a major institution, as well as contributing to a wider public debate on collections and whose heritage is being preserved.

As a psychotherapist with a background in the visual arts, I have written the texts for all our card sets to date, freely associating to the images with an aim of lifting out topics linked to fostering a greater understanding of self/other relationships. This current project was different. As it came about as part of Future Collect’s commitment to public engagement, A Return to Breath and Making that remembers… were produced as limited editions of printed sets of cards for the artists and programme partners. To ensure these resources had the widest possible reach, we also produced them as our first digital sets.

In contrast to our previous resources, both A Return to Breath and Making that remembers… focus on a body of work rather than a range of practitioners and media. This made it possible for a dialogue to evolve between myself and the two artists Jade de Montserrat and Maria Amidu, Future Collect’s Curatorial Project Manager Rohini Malik Okon and iniva’s Director, Sepake Angiama. As a white Canadian, my contributions reflect aspects of my family history including ‘stories told and untold’ of migration with the attendant emotional and psychological losses familiar to those who (in)voluntarily leave their birth country behind never to return. My own ‘back and forth-ness’ which eventually led me to settle in London may be seen in part as an attempt to make sense of the gaps that cannot be filled with ‘knowing about’.

Although the text composed for the cards came about through collaborative processes, the themes I draw out in this piece of writing, the emphasis given to certain interpretations, and the descriptions included are mine and may not reflect the artist’s. Also, as we know, perspectives can and do change, even over a short period of time.

James Northcote Ira Aldridge as Othello, The Moor of Venice, 1826 Oil on canvas 76.2cm X 63.5cm © Manchester Art Gallery

A Return to Breath is the title of a series of twelve watercolours Jade de Montserrat made as a component of her Future Collect commission at Manchester Art Gallery in response to James Northcote’s 1826 portrait of the celebrated African American actor Ira Aldridge held in the gallery’s collection.

Northcote depicted Aldridge in the role of Othello who was characterised by Shakespeare as a Moor, a term used to describe people with dark skin colour living in Europe between the 15th and 17th centuries, now seen to be dehumanising shorthand. Perhaps informed by the Spanish Moors who were former Muslims forced to convert to Christianity or be exiled after Spain outlawed Islam in the early 16th century, some contemporary interpretations of the play raise the possibility that the ‘Moor of Venice’ was a closeted, practising Muslim. (See Richard Twyman’s 2018 production A Moor for Our Time – English Touring Theatre) The reasons behind Othello’s migration from North Africa to Venice are left unanswered, as is the case in many families with dislocation in their past. Why did he leave, and did he have a choice? What did he experience on the way? What personal or enforced losses did he incur? Was religion one of them? How did he navigate belonging and ‘unbelonging’? Did he ever find his place in Venice?

Othello, who is caricatured as a ‘wheeling stranger’ (that is, an outsider) and ‘an erring barbarian’, is also described by Iago as ‘fall’n into an epilepsy’. This combined with Othello’s emotional unrest and self-doubt, simultaneously caused and compounded by the racism and prejudice he experienced, can be seen as a form of disability linked to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a condition now characterised as neurodivergent. Although first introduced in the context of autism, the term has grown to encompass far more and takes into account race, gender, class, sexual/gender identity as well as any other acquired mental disabilities. The mutually impactful forces of colonialism, empire building, racism, and experiences that leave behind a disability, all themes that feature in Othello, are explored in depth by Amrita Dhar in her chapter ‘Shakespeare, Race, and Disability: Othello and the Wheeling Strangers of Here and Everywhere’ in the Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare and Race (2024).

In ‘Shame and Black Identity Wounding’ included as a chapter in Shame Matters (2022), psychotherapist, supervisor and organisational consultant Aileen Alleyne says “Colurism/shadism, which has always been a political and commercial issue, continues to contribute to complex issues of not being good enough. Put quite simply in this Caribbean rhyme, ’If you’re white, you’re right; if you are brown stick around; if you are black, get the hell back’.” Alleyne goes on to define Type III Complex Trauma as historical and collective or intergenerational giving examples which include racism, slavery, forcible removal from a family, community or country, genocide, and war. As she notes, the resulting pain and distress caused by PTSD may well occur at the intersection of gender, race, class, ethnicity, sexuality and disability. The legacy of shame (bacp.co.uk)

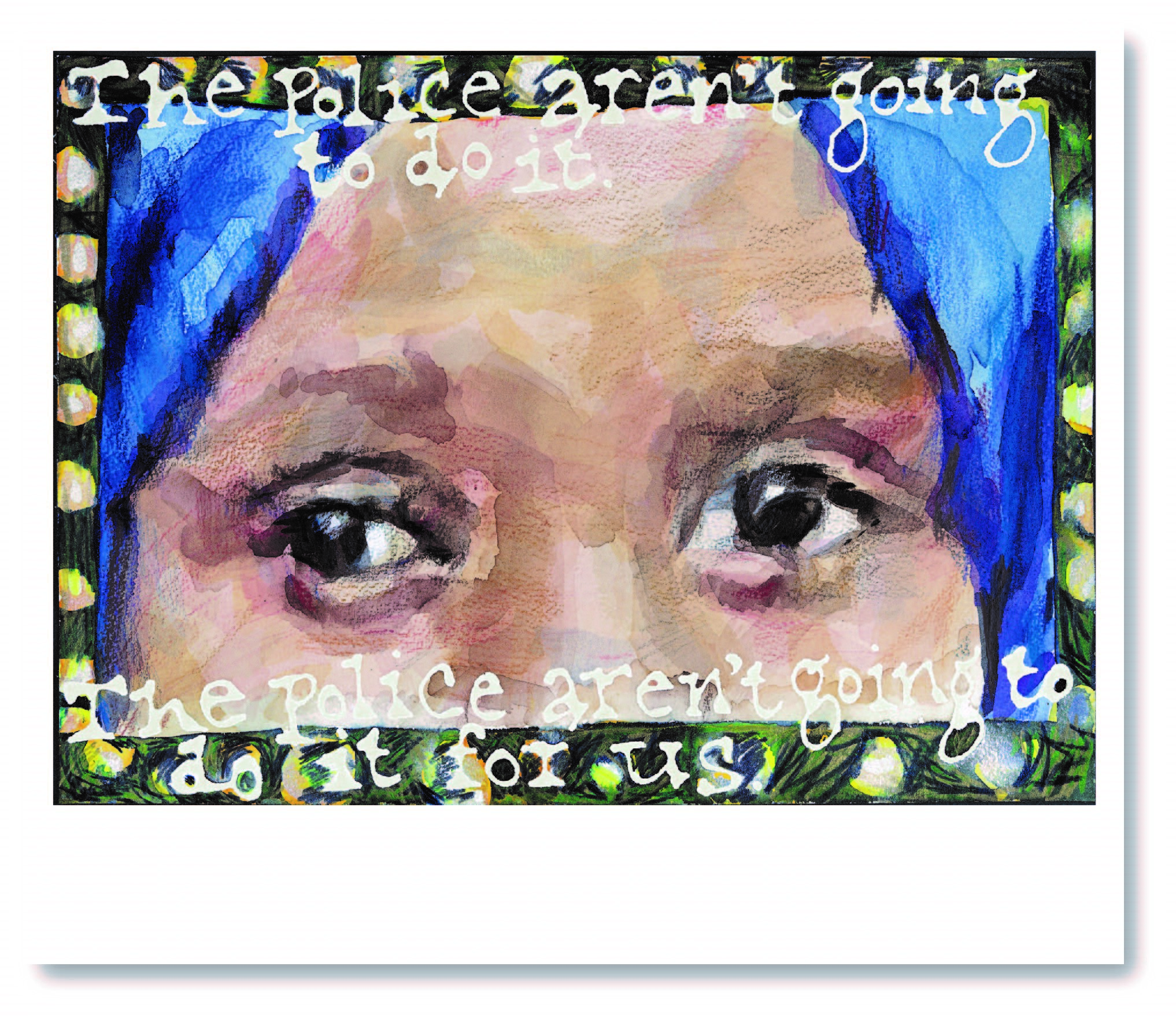

The character of Othello, multi-dimensional and multi-layered, and many of the themes in the play itself, remain compellingly relevant. Shakespeare’s exploration of cultural and personal identities and meanings; social, relational and institutional structures of power; the impact of racism and discrimination, embodied histories, and the ethics of care (that is, the moral importance of meeting people’s needs) are resonant subjects that also weave their way through A Return to Breath. Jade’s mixed media watercolour of Ira Aldridge, in common with four other works in the series, homes in on the subject’s eyes alone which calls to mind another dimension of (Black) identity wounding, that of the gaze: Who is looking at whom and through what lens? What systems of power are being played out? How does the act of looking inform meaning and interpretation? In what circumstances might we feel a sense of being recognised and understood? When we direct our gaze inwards, through whose eyes are we seeing ourselves? Based on this, what stories do we tell ourselves about ourselves? Which plotlines or characters are over-written, re-cast, edited out or ‘forgotten’ and why?

Return to Breath

Photograph: Jade de Montserrat

Image Layout: Sonja Frick

Jade’s line of sight moves from the distant to the more recent past, drawing our attention to individuals in the public domain who have been the recipient of society’s indifferent, prejudicial or discriminatory gaze with tragic results. Sarah Reed, one of Jade’s subjects, took her own life in 2016 while on remand in Holloway prison due to failures in the system and a lack of understanding of, and care for, her mental health needs by some of the prison staff, which many believe was influenced by racism. Where might the line of accountability lead? As Sarah Reed’s death was the result of systemic failures, who is complicit or culpable by implication? More generally, what does her suicide say about incarceration? Centring emotional wellbeing and the ethics of care at every level of society means shifting the emphasis from punishment to rehabilitation and transformative justice – whose responsibility is it to bring this about?

Although on the surface, Maria Amidu’s finished pieces and works in progress might seem to have little in common with A Return to Breath, there are some points of overlap. One of the key themes recurring through Making that remembers… a correspondence between emotion and materials is how our inevitably partial or skewed, yet emotionally truthful, recollections of personal and shared histories leave an indelible mark. When working on her Future Collect commission with Towner Eastbourne, Maria came across paintings in their collection by Anneliese Holles, an artist who infuses ordinary objects with mystery, ambiguity and multiple meanings. The subject of Holles’s painting below, selected by Maria, is a dressing table, a once popular piece of furniture which often included a ‘skirt’ of pleated fabric for decoration.

Floating ghost-like against a deep blue background, Holles’s depiction may hark back to her own childhood in the 1960s, a time when, in some homes, women might have sat at just such a dressing table to do their hair and make-up. Holles seems to capture the way in which memories can drift in and out of focus, phantom-like, bringing in their wake feelings and thoughts that connect us to our past in ways that can be comfortingly familiar or somewhat unsettling, perhaps putting us in touch with grief or loss.

Anneliese Holles Recollections: Dressing Table, 1997 Oil and acrylic on canvas 92 x 107 cm

Towner Collection, Towner Eastbourne ©The Artist’s Estate

Alongside Holles’s own associations, which we can only guess at, this particular piece of furniture might have been chosen by her as an apt subject because of its gendered history. Perhaps Holles is encouraging us to reflect on what a dressing table says about some of the unrealistic, socially constructed expectations placed on women to ‘perform femininity’ (as defined by American philosopher Judith Butler in her seminal text Gender Trouble, 1990) and to question whose wishes are fulfilled when these standards are conformed to. Holles grew up in the 1960s when the second wave of feminism, termed the Women’s Liberation Movement, took hold. Exploring her painting through this lens may prompt us to wonder how girls and women of different generations and cultures negotiated their family roles and relationships in the context of these social shifts.

In common with Holles, Maria also looks to the everyday to spark connections that might otherwise elude us. In a film still included in Making that remembers… daylight filtering through a white muslin curtain creates an intriguing play of shadows. Whatever lies beyond remains tantalizingly obscured.

The title – 1973, still (home) – hints at an autobiographical intent but without any context or additional content, we are left with a sense of the missing, perhaps bringing to mind something or someone lost at any early age before a more defined memory could be laid down. An image such as this, steeped in both the ordinary and the mysterious, can act as a blank canvas onto which we project scenes or associations linked to our own past. The absence of visual cues allows our imagination free rein bringing the possibility of contact with the ‘unthought known’, as psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas termed the felt impressions we intuit but cannot readily describe.

Such emotionally imbued imprints leave traces in our memory, just as Maria’s art making process shows us. Her photographic image entitled 26,778,780 minutes, work in progress, 2023 captures her hand immersed in a vat of paper slurry made up of pulped abaca fibre dispersed in water. The movement of the water becomes a ‘hidden’ part of the handmade paper, with the fibres once dried, a tangible record of the process.

Moving through our unconscious, forming and re-forming like the abaca fibres in Maria’s paper slurry, are disowned feelings and thoughts about ourselves as well as our fears, desires and buried histories, some unarticulated but not unforgotten. Co-mingling the individual with the collective, this emotional inheritance can include transgenerational trauma which if unacknowledged and unprocessed, continues to be passed down the line.

Unless we step back and observe our inner thoughts, we may be unaware of the ways in which such psychic residue and familial, institutional and psycho-social systems of power continue to shape us. Whose voice is heard, whose opinions matter and whose choices are valued are all as relevant in the family setting as in the wider social context and just as impactful. The messages we give to ourselves about ourselves are formed early on. Even our interactions with primary caregivers in our infancy leave us with ‘felt experiences’ which, in turn, influence our sense of self for better or worse.

Both artists and psychotherapists share an interest in the dynamic relationships between inner and outer realities, ‘fact’ and fantasy, past and present, the known and the ‘known unknown’, and self/other-authored narratives. This complex intermingling and layering of the conscious and the unconscious suggest that meanings are never fixed but continue to evolve over time. A Return to Breath and Making that remembers… a correspondence between emotion and materials bring these ideas to life in unexpected and evocative ways, reflecting, disrupting and challenging our worlds within and without in equal measure.

Related reading

- Aileen Alleyne: The Internal Oppressor and Black Identity Wounding, published on the Black, African and Asian Therapy Network website, June case notesFS (baatn.org.uk)

- Aileen Alleyne Chapter 5 in Shame Matters | Attachment and Relational Perspectives for Psychothera (taylorfrancis.com)

- Christopher Bollas | Institute of Psychoanalysis

- Introduction | The Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare and Race | Oxford Academic (oup.com)

- Emotional Inheritance — Dr. Galit Atlas Psychoanalyst Galit Atlas has written this book for the general reader

- Bringing Our Histories into School-Based Therapy | How Therapists’ Bac (taylorfrancis.com) This recently published book (2023) co-edited by Lyn French and Reva Klein looks at how therapists’ backstories enrich their work with children and young people.