Iniva Creative Learning is very pleased to announce the upcoming launch our 6th set of Emotional Learning Cards in September 2016, entitled ‘What do relationships mean to you?’ Exploring sex and intimacy, this new resource will be of use to psychotherapists, couple therapists and teachers/ educators who deliver Sex and Relationships (SRE) lessons (more information coming soon).

In our current blog, Lyn French (A Space Director) starts us off by highlighting some of the key themes reflecting the politics of gender. To find out more about our new cards contact us, join the mailing list or follow our social media feeds.

As we move through childhood and early adolescence, we become increasingly conscious of what is commonly called ‘selfhood’. The self is simply a convenient term referring not just to one singular, discrete entity but more to a sense of who we are which arises from the conscious and unconscious meanings we give to our life and to our experiences. We use words to describe ourselves to ourselves and to each other. Through the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves, we consciously and unconsciously write and re-write our personal narratives, both discovering and creating who we are in the process.

In the mix will be gender and the complicated social, political and familial history of roles, traits and qualities attached to the labels ‘male’ and ‘female’. We are all formally assigned a gender at birth. In fact, many parents choose to be told their baby’s gender even before its born. Early on in pregnancy, most parents begin to develop a relationship with their unborn child which includes imagining what he or she will be like. This continues after birth when parents are getting to know their baby. Gender has a significant role to play in this process. Society gives us overt as well as subliminal messages of what boys and girls could, should or might be like. These ideas are biologically, culturally and socially informed. Until more recent times, it was automatically assumed that biological differences determine gender identity, thinking which privileges the physical body and gives no weight at all to what an individual actually feels. As gender shapes the roles which society permits or denies to boys and men and girls and women, such thinking is bound to be problematic in today’s world and continues to be challenged by feminists, LGBTQ activists and various social movements.

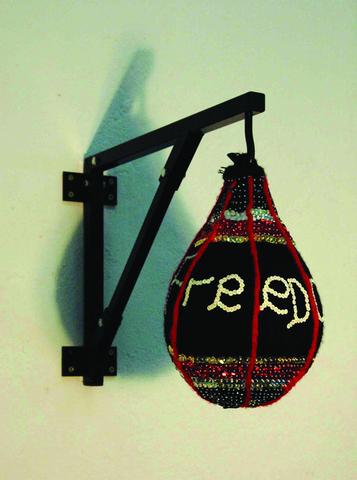

Monica de Miranda – Freedom (2006) – Found within What do you feel? Image courtesy of the artist.

Monica de Miranda’s image ‘Freedom’ included in our set of Emotional Learning Cards entitled What do you feel? cleverly disrupts gender stereotyping. She’s made a knitted cover for a punching bag onto which she sewed the word ‘Freedom‘ using white sequins. Knitting, sewing, crocheting and embroidering are all activities traditionally associated with women. As the end result is usually a piece of clothing or something like a blanket, these activities are usually seen as an extension of care-giving. Knitting is by its very nature a solo activity which is more passive than active in nature. Contrast this with what a punching bag commonly symbolises and you can see how ideas about gender are being subverted in Monica de Miranda’s piece.

We know from evolutionary psychology that the brain evolved in response to problems encountered by our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Evolutionary psychologists suggest that gender role division came about through attempts to deal with the very real challenges faced by the earliest human communities. Over time, men and women evolved to occupy different social roles with the division of labour shown to be an advantage ensuring survival as well as reproductive success. Some think this hereditary history contributes to why men and women differ not just in the roles they are assigned but psychologically too.

Winding the clock forward, we see how our social and relational environment has changed significantly since the dawn of the human family. In the West, philosophers, social theorists, psychologists, psychotherapists and more recently neuroscientists have been interested in the conscious and unconscious forces which shape identity and in the theme of consciousness in general. One of the original attempts to describe consciousness is attributed to John Locke, specifically his ‘Essay Concerning Human Understanding’ which was published in 1690. In it, Locke defined consciousness as ‘the perception of what passes in a man’s own mind’. However, we know from psychoanalysis that much of what goes on in the mind is unconscious. Artists, in common with psychotherapists, often aim to make the unconscious conscious.

Take Kimathi Donkar’s painting ‘When shall we 3?’ from the A to Z of Leadership for example. It is one of a series exploring powerful yet complex black women who helped define our contemporary world. Each painting in the series, entitled ‘Queens of the Undead’, depicts a historic female commander or royal figurehead from Africa or its Diasporas, celebrated for their place in liberation struggles. Rainha Nzinga of Matamba, the seventeenth-century Mbundu monarch who fought Portuguese armies in Angola, is the main protagonist in ‘When shall we 3?

Kimathi Donkor – When Shall We Three (2010). Found within the A-Z of Leadership. Image courtesy of the artist

Rainha Nzinga was given the power to rule after the suicide of her brother as her brother’s son, the rightful heir, was too young to take on the position. Even if one knows nothing about her role in the fight against Portuguese armies in Angola or about the historical context being referenced, When shall we 3? can be read through the filters of gender, race, power and politics. Donkar has made his painting relevant to today’s world by representing the figures as contemporary rather than historic. The dynamics alluded to in his work raise questions about the relationships between power, ambition, equality and oppression, all layered with gender politics.

Gender again takes centre stage in Halil Altindere’s image entitled ‘Mirage’ also from the A to Z of Leadership. Here we see a woman seemingly looking down on a man whose head is literally buried in the sand. Is she gazing at him with an air of compassion? Criticism? Derision? Confusion? Something else altogether? It’s impossible to tell. As a viewer, we’ll bring our own associations to the work. However, the very fact that the figure in the more dominant position is a woman means that interpretations can easily carry conscious or unconscious echoes of the mother/ child relationship.

Halil Altindere – Mirage (2008) Found within the A-Z of Leadership. Image courtesy of the artist

Whatever our family constellation, we all have a mother-figure who would have loomed large in early years. For young children, the mother is a very powerful figure whose love is sought and its withdrawal feared in equal measure. The maternal object plays out in gender politics in complex ways in part because we all carry our childhood history in mind. Numerous versions of parental figures reside deep in our unconscious mind. We all create potent images out of our childhood memories. Common characteristics assigned to parent figures, often along gender lines, include the loving one, the care-giver, the with-holder, the betrayer, the forgiver, the rule maker, the unobtainable object of intense desire, the feared one and so on. In adult life, we unavoidably read people through the filters of the past. Becoming conscious of the associations, fears and desires we attach to the labels ‘male’ and ‘female’ is the first step towards letting go of limiting definitions and moving on to a more equal playing field.

To keep up to date with Iniva Creative Learning’s activities and hear more about our upcoming set of cards What do relationships mean to you? join our mailing list or follow our Twitter feed.