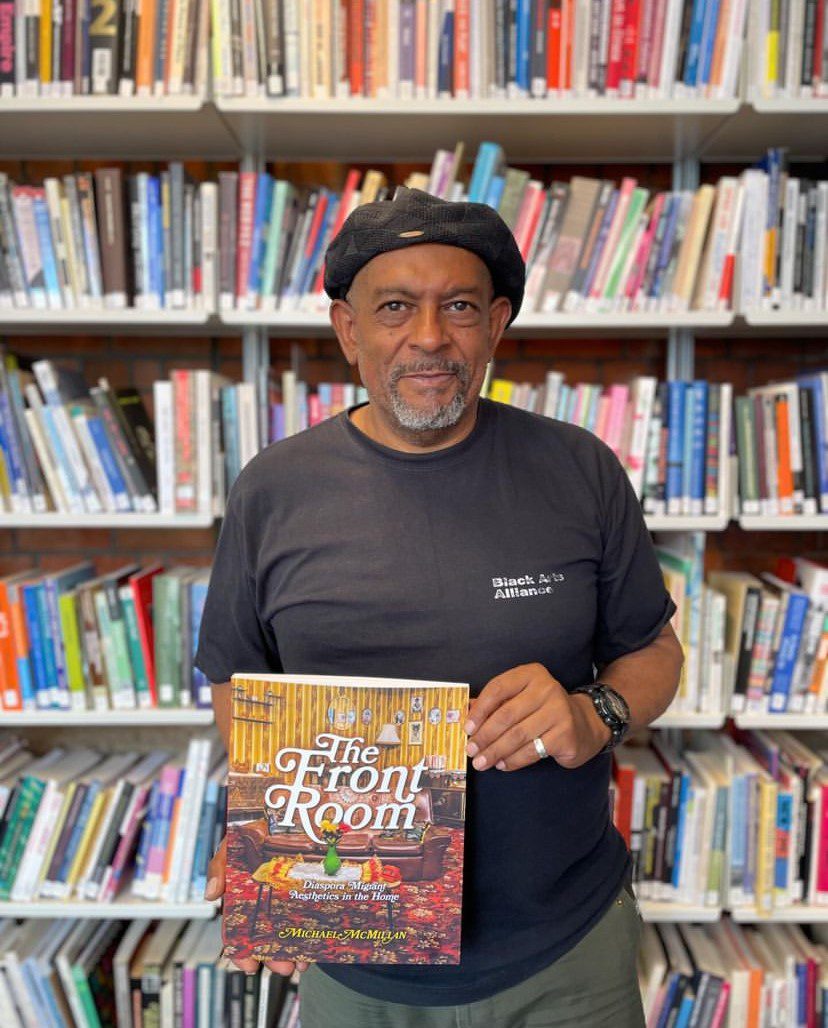

Michael McMillan in Stuart Hall Library, June 2024

Our recent archive volunteer Cassia Clarke reflects on the practice of Michael McMillan and the connection with her Caribbean heritage.

Michael McMillan is a British-born playwright, author, artist, curator and educator of St Vincent and the Grenadines heritage. Since the early 2000’s, McMillan has become a prolific installation artist depicting the West Indies domestic interior of working-class respectability. These simulated spaces include, but are not exclusive to –

- The West Indian Front Room (2003), Zion Arts Centre/BAA, Manchester.

- The West Indian Front Room: Memories and Impressions of Black British Homes (2005-06), Geffrye Museum, London (renamed the Museum of the Home in 2019).

- The Living Room of Migrants in the Netherlands (2007), Imagine IC, Amsterdam.

- A Living Room Surrounded by Salt Installation (2008), Buena Vista, Curacao

- The Front Room ‘Inna JoBurg’ & The Arrivants (2016), FADA Gallery, University of Johannesburg.

- Joyce’s Front Room, 1970 (2021), Tate Britain, London – a part of a group show, Life Between Islands, Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now.

- A Front Room in 1976 (2021), Museum of the Home (formerly the Geffrye Museum).

- The Front Room: Inna Toronto/6ix (2023) Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto – a part of a group show, Life Between Islands, Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now.

I was introduced to Michael McMillan and his installation work through Tate Britain’s group show, Life Between Islands (December 2021 – April 2022), titled Joyce’s Front Room 1970. The exhibit was split into five sub-themes: Arrivals, Pressure, Ghost of History, Caribbean Regained: Carnival and Creolisation and Past, Present, Future. McMillan’s front room was positioned in Pressure with connections to Arrivals. ‘Pressure’ was dedicated to artists who either migrated to the UK as children or were born in Britain, whose work highlights togetherness and strength within the struggle. ‘Arrivals’ represented the reclamation of African-Caribbean heritage intertwined within the ingrained values of their ancestors’ colonisers. Joyce’s Front Room 1970 was the temporary iteration of the permanently reconstructed 1970s front room at the Museum of the Home. Each front room in the series is moulded after a fictitious person or persons that tells a kind of truth about the West Indies lives in their colonial mother country.

Seeing McMillan’s work for the first time, I was curious to find out why he does it. The voyeuristic and intrusive nature of placing a private space, the front room, into an indefinite public space, and recasting ownership to an institution needed to be unpacked. The Front Room – Migrant Aesthetics in the Home, published originally in 2007 and revised in 2023, touches on the individual assembled elements and its social and cultural values, however, I do not recall much on the reasons for the series’ curation within the institutions. Communicating with McMillan about his installation practice I learnt of his intention which greatly informed my dissertation that attempted to understand his front room series through a curatorial care lens.

“Apart from the fact that I was born in the UK with parents of Vincentian migrant heritage, the permanence of The Front Room within the Museum of the Home is politically significant in terms of Black British identity and belonging. Towards decolonising the museum, it moves beyond the temporal trope of Black History Month, every October, as it signifies that Britain is our home.” – Michael McMillan interviewed by Cassia Clarke (2022)

Following the completion of my dissertation, I have kept up-to-date with McMillan’s work. In August 2023, I attended his talk at the V&A, The Front Room Portraits: Diaspora Migrant Aesthetics in the Home, and since January 2024, I participated in McMillan’s 6-week course at the V&A, Look We Here Curating the Caribbean. Upon reflection, I see why I have gravitated towards his work – to understand, or at least try, the culture and heritage of my parents, grandparents and so forth. My parents’ assimilation into British culture had its ripple effect. It created me, a person who would be considered a foreigner in my family’s mother country, Jamaica. Following McMillan’s work and associating with like-minded people affirms my heavily British, Caribbean adjacent existence.

Biography

Cassia Clarke is a Luton-born British-Caribbean self-taught archivist, researcher and facilitator. She uses an autoethnographic and co-curatorial approach to engage greater knowledge democracy and collective intervention to better our accessibility to institutionally held knowledge. Cassia’s project, ‘Take My Word For It’ aims to confront a gap in the knowledge and material exchange between GLAM institutions (Gallery, Library, Archive, Museum) and the community to assist the preservation of physical photographic archives within the home.