‘Kalika’ by Prafulla Mohanti

Independent Writer and Curator Shalmali Shetty reviews Prafulla Mohanti’s artistic practice, influenced by his lived experiences between India and the UK, in context to iniva’s current exhibition titled Village Letters showcased at the Stuart Hall Library

An egg, its yolk; an eye, its pupil; a yoni (womb), its seed; a bindu (dot), a shunya (zero), a mandala (circle), a globe in a fathomless Brahmanda (universe); the purusha and prakriti (union of masculine and feminine to create a non-binary energy) with no beginning or end: ananta (infinite); paripurna (complete) – each painting emanated a strong energy, while the simultaneous experience of everything and nothing pulsated across the room. Our exchange of stories and conversations began making visual sense.

Time

Prafulla Mohanti’s studio in London is an archive of his long-drawn practice. He remains to be one of the last living artists from the neo-Tantric movement of the early 60s to late 80s, that spread within both the Indian and Western modern art contexts. The studio was otherwise occupied by dusty wooden furniture strewn with piles of books and posters, rolls of paper and flattened cartons leaning against the pink walls; intricately designed moth-eaten rugs warming the wooden floors, lengths of printed fabric covering surfaces; canvasses, easels and paint; framed pictures, bronze sculptures and idols of deities, interspersed with lopsided lamps and vases of fresh flowers… each item carried with it the damp scent of memories and lived experiences from across geographies and cultures. Slowly ambling our way through the room, Prafulla gathered some books and pulled a length of hand-painted fabric around his neck, ready for the opening of his solo exhibition titled Village Letters.

Leeds

Showcased at the Stuart Hall Library, Village Letters is curated by iniva’s curator Beatriz Lobo, who found affinities in his experiences as an immigrant from the Global South – after having previously come across a body of his works displayed as part of Hepworth Wakefield’s 2021 exhibition titled Prafulla Mohanti: Full Circle, that included his works from their acquisitions after a show in the 1960s. An indispensable component of the ongoing exhibition are six of Prafulla’s published books – My Village, My Life: Portrait of an Indian Village (1974); Indian Village Tales (1975); Through Brown Eyes (1985); Changing Village, Changing Life (1990); Longing: Poems (2004) and Shunya: Prafulla Mohanti, Paintings (2012). Through folios from each book displayed adjacent to them, the viewer is sensitively introduced to the contents of each publication that revisit his lived experiences between the two geographical landscapes of India and the UK, linked through histories of colonialism and capitalism. Paper, canvas and textile works, line the inner walls of the library, leading the viewer to a documentary on his life and practice. His narrations, both in-person and through his books, carry honest and humorous accounts of his fear, surprise, ignorance, innocence, friendships, and personal reflections, interspersed with tales from his home village of Nanpur, Odisha (India).

Strangers

Prafulla moved to England as a student of architecture in 1960. His idols, along with an image of the deity Jagannath, some personal belongings, and his stories were all he could carry with him from India. His persisting nostalgia and memories of the village bring back the smell of rain coupled with the love of his mother, and illustrates a life based on customs, traditions, superstitions and hardships. But the village he would go back to some years later, would have started to show early signs of global development – the construction of the first bridge across the village river; the sudden introduction of the clock challenging the ambiguity surrounding a sense of time; or the introduction of electricity and the setting up of industries – having pernicious effects and gradually erasing a rural way of life. The self-sufficient village would now oscillate between traditional belief-systems and modernist aspirations, replicating forms of unskilled labour exploitation, poverty and homelessness – conditions he repeatedly encountered in urban cities such as Bombay and across England.

East End

Are you black?’.. ‘No, I’m brown’.. ‘Light or dark?’.. ‘Is the colour of my skin important?’

The Commonwealth Immigrants Act was passed in 1962 by a racially-driven Conservative Party, controlling movement between borders – ironically towards a country that was otherwise within the clutches of the British Empire for almost three centuries. Based on his skin colour, Prafulla began facing forms of systemic racism and discrimination in his workplace and everyday living, ingrained in the British society deeper and darker than the apparent brownness of his skin, and colder than the grey buildings and clouds that consumed the cities. During this time, also termed as the ‘Swinging Sixties’, Britain was undergoing significant changes socially and culturally, with the emergence of a youth-driven revolution upholding progressive thoughts, liberal and modernist views and challenging conservative establishments. These countercultural movements, while resisting capitalist cultures, aided the spread of Orientalist ideas and spiritual practices of yoga and the esoteric Tantric traditions (that had previously also aided the Indian Independence movement), although warped in its Western interpretation and reception. Prafulla however was not able to escape a harrowing racist attack as a consequence of the anti-immigrant law, that necessitated him to return to his village for a period of healing.

Grandparents

Reading through some of his writings, I personally resonated with innumerable experiences of living between India and the UK. What is it to migrate to another country, away from your own to learn and unlearn? Sixty-three years since he moved to this country, three years since I have – yet some of our experiences uncannily overlap. I remembered one of my first thoughts after a minor, yet nerve-racking racist incident – in this country, I not only have to be conscious of being a woman, but also, brown, leading to a tenfold increase in the resulting experiences.

Coming from a culture that accords compassion to strangers, receiving them as guests – Prafulla felt an acute sense of isolation living in the largely individualistic society of England, and often found himself walking around the East End of London to find comfort in communities, friendships and sharing. An instance of his community-driven values comes across in an anecdote, where once as part of a town-planning project he proposed to design a housing estate, ensuring each house came with a self-contained flat that could allow grandparents to live with their grandchildren for mutual support; however, only to be dismissed by his British seniors. In a contemplative act of revisiting skills he grew up with and the values he wished to propagate, he decided to start painting and teach dance, developing a practice that connoted a utopian optimism – where there is only love, care, sharing and healing.

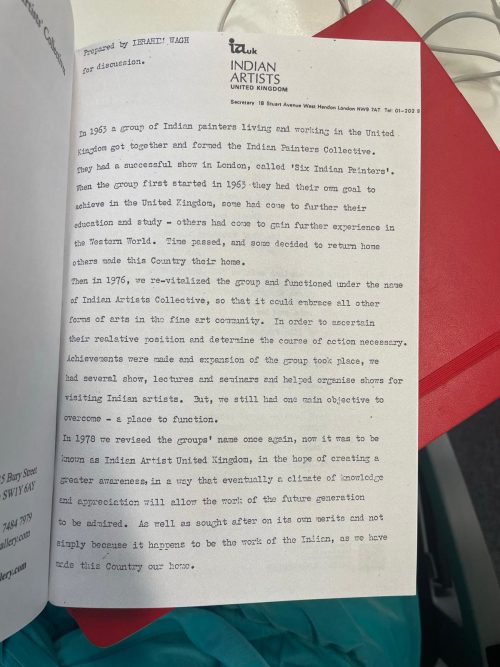

IAUK_1

A prolonged meditative gaze at his paintings to then close my eyes and experience phosphenes – further, a blob of bright, liquid yellow paint spread thick on a wet paper, spiking outwards and edging to the margins. I watch frowning, slightly troubled that I am unable to control the outcome. Some days we would engage in form drawing using a thick crayon on paper, going over the pattern until the page was covered with the thickness of repetition. Some days we would practice Eurythmy – repeatedly moving in formations, collectively expressing through our body in a simultaneous act of feeling everything and nothing. Memories from my school resurfaced as I listened to Prafulla while he gently swayed his hands creating patterns in the air. Based on anthroposophic philosophies and teachings, my school followed a Waldorf curriculum that ensured pupils learned through individual freedom, healing and practical utopia.

IAUK_2

Prafulla explores his utopia instead through neo-Tantrism. Neo-Tantra, a term coined by the Indian writer and curator LP Sihare, shares affinities with the spiritual practice of Tantra, a syncretic and ritualistic doctrine prevalent since the 5th century AD, across Hindu, Buddhist and Jain philosophical teachings that engages the body and mind through metaphysical acts, alchemy, mysticism, meditation, sacred symbolism, geometric abstraction and numerical diagrams, in the prospect of evoking cosmic energies and astronomical vibrations. Although today the term Tantra may connote negative associations with black magic and the cult of ecstasy, the tradition has had a layered and complex history of evolution over the centuries. Biren De was one of the first artists to reference Tantric imageries in his paintings, followed by a group of artists including KCS Paniker, J Swaminathan, Acharya Vyakul and Prafulla himself. A number of exhibitions showcased works of neo-Tantric artists in India, Europe and the Americas between the 60s and 80s, marking a significant emergence and response to Indian modern art. Tantric practices have also had a considerable influence on the works of abstractionists such as Paul Klee, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko and Kandinsky, amongst others.

IAUK_3

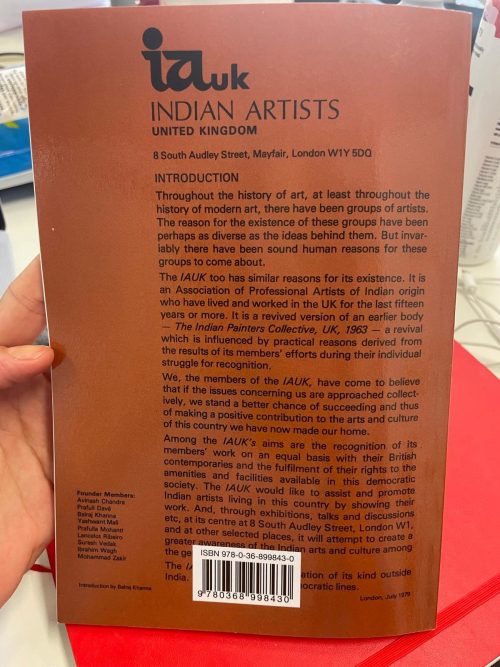

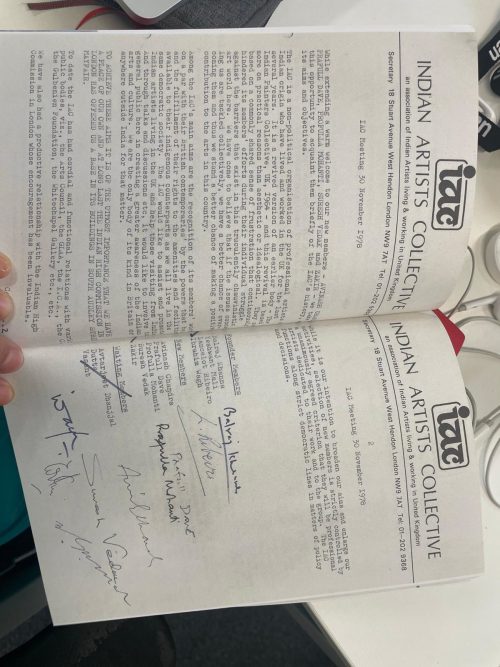

Prafulla’s practice echoes the ongoing impacts and weight of experiences that his brown body has been put through in the wake of post-colonial frameworks both within India, and the UK’s discreet approach to undoing these models. In 1963, Prafulla and a group of artists founded the Indian Artists United Kingdom (IAUK), later revived in the late 1970s to support the fine artist community from the Indian subcontinent and diaspora. He continues to travel between London and Nanpur, encouraging his British friends to engage with his village community. Some years ago, he and his close friend and partner Derek Moore started a development and education programme for the benefit of the people of the village and further initiated ‘Friends of the Village Nanpur’, an international group of supporters to build on his intentions. Every year, Prafulla visits India to oversee the Nanpur Utsav, an arts festival held during February. In November 2022, he was bestowed with the prestigious Sahitya Akademi Honorary Fellowship in New Delhi, for his outstanding contribution to literature.

About the writer

Shalmali Shetty is a curator, writer and artist working between UK and India. Her research interests include themes of archives, memories, hauntology and material culture studies. She intends to coalesce her backgrounds in art practice and theory in the production of the curatorial.