On 16th May 2022 we organised the study day Contained Terrain: conversations about collecting natural histories, at the Stuart Hall Library. In this generative, open and nourishing space we came together to share and exchange experiences, ideas, research and practice inspired by the themes artist Emii Alrai is exploring in her work around natural histories and landscapes as well as time and memory. We asked what happens to natural artefacts when they are placed in collections, and considered the meaning of containment in relation to entities that were once subject to change, decay and life processes, becoming frozen into something static. With the act of containment also suggesting colonial implications of ownership and capture, we explored what it might mean to decolonise natural collections and reflected on new models for the form a container or collection could take.

To create a record of the day we invited artist and writer Pear Nuallak, a participant at the study day, to produce a written and visual response. We are delighted to share their poetic and evocative reflections below.

To see further information on the study day including the bios for all of the collaborators who joined us in a process of thinking together, see the study day info pack here.

***

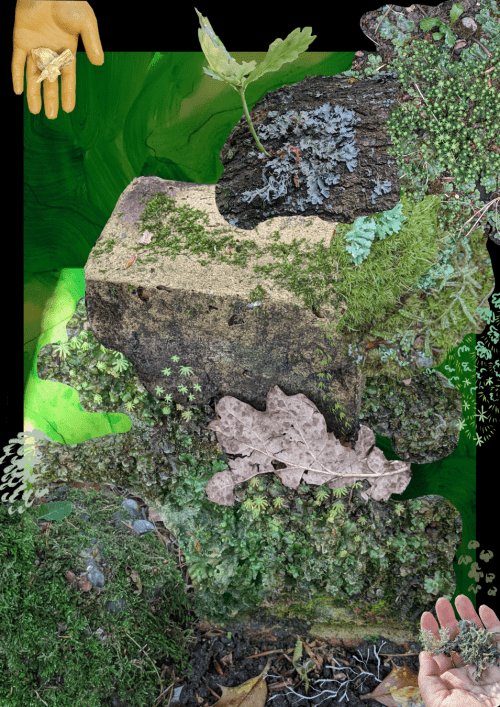

Digital collage in response to the Future Collect study day in May, with digital mark-making, mosses and lichens from Croydon, and a tiny plastic hand bearing frankincense.

1. On the archive

Let us consider the archive as a container. Before we even examine the objects contained within this archive, we might ask: what are the materials, textures, and surfaces that hold these objects? And does the nature of the container change the nature of the object?

The same material can offer contrasting languages:

the cold perfection of a vitrine [clear, sharp, neutral, objective]

or

{memory scarring once-liquid surface} hand-blown glass

If an archive is a container, what else can contain and be contained?

Container as in earth (holding and releasing)

Container as in river (holding and releasing)

Container as in body (holding and releasing, holding and releasing, holding and releasing—)

Think of a body.

A head, torso, four limbs, and balanced senses all working to order: the embodiment of rationality. I suspect this is not the body we’re thinking of; we are likely thinking of our own bodies, what we can and can’t do, unique aches and pains. Parts we understand without verbal language, or perhaps parts misnamed and miscategorised by others; parts we have yet to know, and maybe parts that document our experience of life in all its sensory horrors and delights.

We map the landscape like a body: talus / heel / foot / scar / cataract.

But how does the land record what it has witnessed?

*

The archive is not a neutral space. As we reflected on the ordered space of the museum, I thought of how Shola von Reinhold’s LOTE dips jewelled fingers into the archive and draws up the traces, revivifications, and wilful erasures of Black people in western European history. Coloniality relies on ascetic leanness, pleasurable ornament pulled away until only dry white bone remains; the appetite for intense sensory experience is simultaneously denied and recklessly pursued, the Other as something to be neutralised but also open for rich, lush pleasure. Containment that desires immersion.

The archive is not a site of absolute power. Its symbolic potency exists alongside its constant construction through human effort; archiving is a process. Objects are forgotten there, wrapped and tucked away, preserved precariously because the purse strings are tight. Archives shift according to internal conversations: objects might be dusted off and paraded forth when cultural tastes change and funds are redistributed.

What if an archive was wholly a place of redistribution? Rather than objects deriving value from its preservation as the cynosure of museum space, an object can be released so that it can continue its life cycle, dissipating and resolving itself. Intentionally returning things to the earth does not mean permanent loss. Killing is not the same as death; permitting things to be redistributed is not the same as neglect or destruction.

***

2. A list of nourishing things:

- picnic (rained on)

- questions questions questions

- tiny butter-scented pastries

- gaps in our stories

- decay

***

3. On Croydon

Croydon is my hometown, a place associated with concrete and failed modernity. But for centuries the Great North Wood stretched over what we now know as Camberwell to Croydon. Before everything was mapped, parishioners would beat the bounds of the parish, using great oaks as markers. As people whipped cut crosses into tree bark, they would prick their thumbs to instil the memory of the route into their own flesh.

The Great North Wood was cut down throughout the 18th – 19th centuries as the gentry enclosed common land, clearing away agricultural communities in order to create their estates. The logic of enclosure—displacement, possession, extraction—is the logic of colonialism. Once the gentry had their fill, what remained of these woods and estates were given back to public use: the hundred of parks, woodlands, and green spaces scattered across the borough comprise Croydon’s natural heritage.

At Coombe Cliff house in Croydon, Frederick Horniman built a conservatory to house his collection of sensitive plants; eventually, this was removed to the grounds of the Horniman Museum in Forest Hill—a place also once covered by the oaks of the Great North Wood. Coombe Cliff gardens was eventually absorbed into Park Hill Park, a still-thriving green space in the heart of Croydon. There’s something here about portability and containment: the oaks of the Great North Wood becoming ships that colonised the world, moving goods and people like game pieces; the plants conveyed on these ships were housed in a glass and steel structure that could itself be packed up and set down another place where the oaks once grew. Containers have their own life cycles.

Croydon’s concrete and countryside attracts and repels: its urban decay is open for use, backdrops for movies and opportunities for land developers; its parks and ancient woodlands become protected heritage, at once placid and wild, untouched yet enclosed. But what I see is humans as a part of nature and nature as something constructed—lichens growing on rubbish bins and noble oaks, human and nonhuman maintenance of woods and parks, moss and liverworts coming up through brick and concrete.

Lichens are symbioses of funguses, algae, and / or cyanobacteria, creating unique structures. Sometimes these symbioses are mutually beneficial; sometimes they are not. Certain lichens, such as oakmoss (Evernia prunastri), are seen as particularly valuable: oakmoss is an adored perfume fixative and indicator of pure air quality. I have walked all over Croydon to find oakmoss and have never found it growing in isolation; I’ve often seen it on roadside oaks, and always nestled alongside numerous other lichens. I collect these grey-green branching structures only when they fall to the ground, but I still do this with care, as fallen lichens become material to be redistributed among plants and soil. This spring, I was delighted to see so much common liverwort (Marchantia polymorpha), which grows quietly on damp ground and helps restore the soil after wildfire, rapidly growing before diminishing once the original vegetation is able to establish itself once again.

When we talk about how humans have always lived with nature, through cycles of decay and rebirth, we do not speak of simple innocence and prelapsarian idyll: we gesture to Indigenous realities, of effort, labour, manifold knowledge systems, ways of owning without private possession and profiteering. Naturalising the greed of capitalist coloniality as “human nature” is useful to the powerful. It paves the way to naturalising logics of possession and hierarchical ordering, obscuring Indigenous knowledges.

We insist on thinking through the dark of the soil, the viscidity of sap, the sprawling plant, the ambiguous symbiote.

Perhaps we are drawn to certain places and materials because we crave how memories flow through material with the same lively richness as water, nutrients, sun and shade. Perhaps we might yield ourselves to them, and see what happens next.

***

Pear Nuallak is a visual artist and writer from London. Their debut book, Pearls From Their Mouth (Hajar Press, 2022), is a collection of short stories and essays about the body, power, and desire. Their interdisciplinary provocations respond to time and place using craft, meandering through a series of playful repetitive rituals and transforming the mundane into objects and images that hover between the folkloric, comical, and eerie. The starting point is land, the tool of inquiry is the artist’s hand, and the material is often wool and paper, whose substance leads back to the histories of the land and human relationships to the natural world. By pulling at multiple threads all at once—race and nation, city and country, human and natural—the material is unravelled, ready to be examined and re-assembled into something queer and interesting.

When they are not writing, knitting, or wandering the woods, Pear co-organises a queer social hub with the Black Cap Community Benefit Society. A record of all this is kept at @pearpiesyrup on Instagram.