Iniva Creative Learning warmly invites you to visit Iniva’s Stuart Hall Library from 22 February – 4 March 2016 where art created as part of our ArtLab project by Shiraz Bayjoo with pupils from Newport and Dawlish schools in North London can viewed. The work was made in response to the instruction from the Department of Education for all schools to promote core British values. To find out more about our ArtLab project, A-Z of Values visit the ArtLab tab in our menu and see more via Twitter.

In our current blog, Lyn French, A Space Director, reflects on the concept of nation-specific values in general and enquires into the questions this raises.

Exploring the concept of shared values, especially those labelled ‘British’, is a thought-provoking exercise. Most of us have personal values or principles that we live by. But if nation-specific values are to be defined, who is best positioned to decide which to prioritise? Is it possible to avoid underlying agendas entering into the mix? Can values ever be separated from political or religious beliefs and ideologies? Debating these questions seems increasingly important given the fact that many of us live in complex and diverse communities reflecting cultures, beliefs and lifestyles which have both points of overlap and divergence. Although there may be no definitive answers to arrive at, the conversation needs to take place as it touches on subjects that reverberate through past and present political, religious, cultural and social systems.

The work of Stuart Hall, the Jamaican born cultural theorist who lived and worked in the UK from 1951, encouraged us to look beyond the soundbites and put the values of democracy, freedom and equality into action. Stuart Hall was never speaking solely as an academic – he had a personal history which fundamentally shaped his understanding of the world around him. He described himself as being born into a middle-class Jamaican family of African, British and, he believed, Indian descent. Growing up in the colonial West Indies as the only member of his family with a much darker skin colour had, he says, a profound effect on his self perception and on how he understood his place in the world. ‘Pigmentocracy’ is a term relatively recently coined by social scientists to describe societies in which social status is determined by skin pigment. Throughout the many ‘pigmentocracies’ across the world, the lightest-skinned individuals are accorded the highest social status, followed by the brown-skinned and finally the black-skinned who are perceived to be at the bottom of the social hierarchy. This form of prejudice may be explicitly played out or unconsciously communicated even amongst family members as Stuart Hall himself seems to have encountered. His genetic inheritance combined to make him stand out within his own biological family as ‘the darkest one’ and all that this implied in the 1950’s and 60’s.

Shiraz Bayjoo – Image for the letter U for Uncomfortable. Found within the A-Z of Emotions. Image courtesy of the artist.

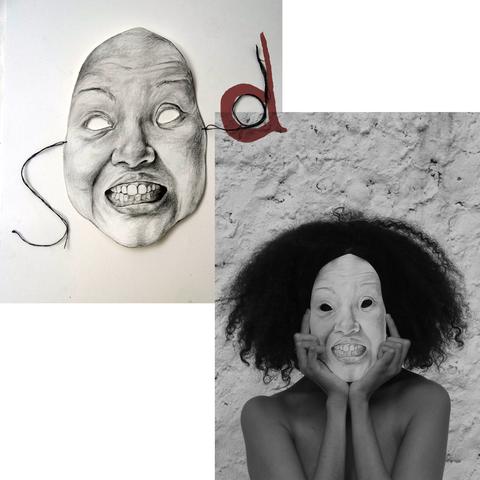

In this image from the A to Z of Emotions, Shiraz Bayjoo depicts a woman of African descent split in two. Perhaps this captures the painful internal split we can all experience if we are seen by our family or wider society as ‘less than’ or fundamentally ‘different’ from how we see ourselves. In such instances, it can seem as if our sense of self is hard to hold onto as we cannot form a coherent or integrated picture of who we really are. It may feel as if our identity becomes imbued with the associations others project onto us leaving us feeling like we’re wearing a mask not of our own making. Or perhaps we believe we have to ‘put on a face’ and comply with the dominant projections in order to be accepted. Phoebe Boswell captures this very well in her drawing illustrating ‘dishonest’ which also features in our resource, A to Z of Emotions.

Phoebe Boswell – Image for the letter D for Dishonest. Found within the A-Z of Emotions. Image courtesy of the artist.

The projections which come our way may be as simple as our family perceiving us as ‘the artistic one’ or ‘the intellectual one’ which may be true in part but not all the time. We might find it hard to let go of these kinds of labels and feel we have to distort who we really are, or who we are becoming, in order to live up to them. Or it could be we are on the receiving end of projections coloured by nuanced stereotypes rooted in our gender, class, race or culture. When our self-image is at odds with how we’re seen by others, the resulting ‘disconnect’ is painful but it can be addressed. We don’t have to collude with the identities others unconsciously give us. As Stuart Hall may have found, by trying to understand this split through making links with others who also carry a divided inner world, we can begin to challenge polarised thinking rooted in ‘them’ and ‘us’ categories. We can make committing ourselves to bringing about meaningful and ‘lived’ equality a core personal value, one which shapes all aspects of our emotional, social and professional lives. This is not as straightforward as it may sound as subtle power dynamics reflecting past histories are embedded deep within our collective psyche and can lead to present day complexities of the kind alluded to in Kimathi Donkor’s painting in the A to Z of Leadership.

Kimathi Donkor – When Shall We Three. Found within the A-Z of Leadership. Image courtesy of the artist.

Kimarthi Donkor’s image alludes to the politics of race and gender but no easy message is conveyed. We are left to find our own meaning out of what is an uncomfortable constellation of figures echoing unresolved dynamics. In her book Mental Slavery: Psychoanalytic Studies of Caribbean People, Barbara Fletchman Smith explores the complex power dynamics we are still living with. The effects of slavery and its impact continues to be experienced by us all. Maybe we carry unconscious inter-generational shame about our history resulting in the belief that we are not entitled to a place at the ‘top table’. Or perhaps, again unconsciously, we feel ‘better than’ because of our light or white skin colour and do not want to give up this inflated sense of self. Barbara Fletchman Smith’s most recent book, Transcending the Legacies of Slavery: A Psychoanalytic View, uses psychoanalysis to unravel what she describes as ‘what was lost, how it was lost and how the loss can be compulsively repeated over generations.’ She forefronts the slave owner’s tendency to separate couples at the first sign of showing a loving interest in each other and of taking infants away from their mothers. Disrupting core relationships like this is bound to leave a raw emotional wound and affect future generations.

Ensuring that children and young people have the chance to develop analytic thinking and acquire skills to reflect more deeply on our shared social, emotional and political life is key. Iniva Creative Learning (ICL) introduced the Art Lab to support this aim. Schools can commission ICL to provide an Iniva artist and an A Space therapist to design and deliver a programme of work exploring a theme identified by the school.

We use contemporary art, research and facilitated discussion to enquire into subjects that concern us all. We want the next generation to feel equipped to move thinking forward on the interrelated themes of gender, race, class and culture, subjects with far reaching legacies which continue to resonate emotionally and pyschologically. Involving young people in art practices as Felipe Castelblanco has achieved in The People’s Island from the A to Z of Leadership and Shiraz has done with Year 4 pupils in Newport and Dawlish schools is not to make artists of all but to spark curiosity, explore meaning making and learn to work collaboratively on shared goals.

Felipe Castel Blanco – The People’s Island A-Z of Leadership. Image courtesy of the artist.

We’d be very pleased to welcome you to the A to Z of Values exhibition at the Stuart hall Library from 22 February to 4 March 2016. If you would like to book a school or group visit please contact us for further details.