- Image: Li Yuan Chia Study Day

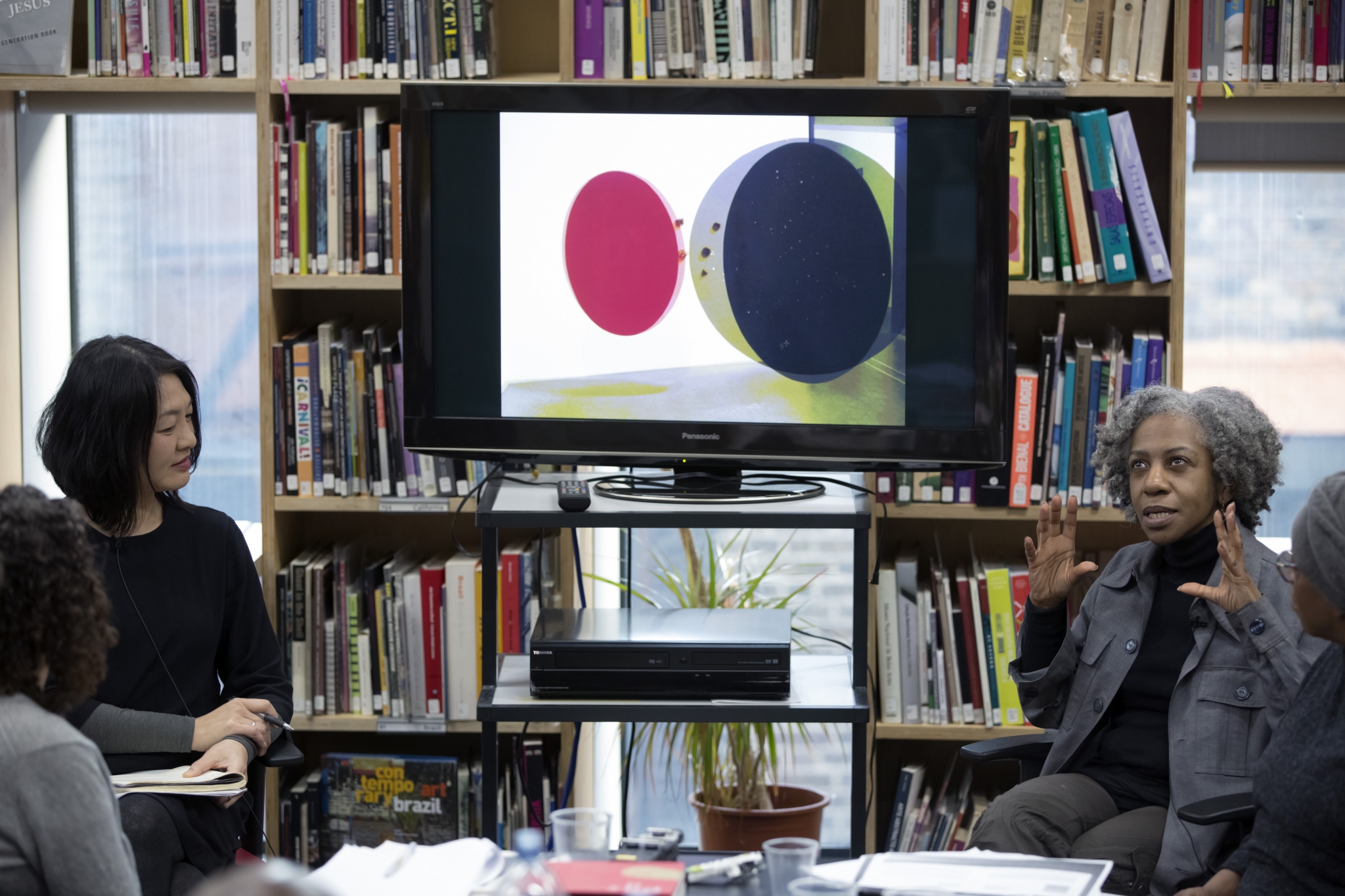

- Image: susan pui san lok (Co-Investigator, BAM) in conversation with Marlene Smith (UK Research Manager, BAM)

- Image: Dr Hilary Floe in conversation with Andrew Wilson (Tate Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary British Art and Archives)

- Image: Yu Wei (PhD candidate, Birkbeck)

A response by guest blogger Nicola Simpson

‘Where can we place the artistic practice of Li Yuan Chia in relationship to Modernism?’

On 13th February, Iniva and BAM (Black Artists & Modernism) co-hosted a study day in the Stuart Hall Library focused on the work of artist Li Yuan Chia (1929-1994) an artist born in China, resident in Taiwan and Italy before settling in Britain in 1966. Over fifteen years have now passed since Iniva organized the retrospective on Li’s work at Camden Arts Centre in 2001, the most comprehensive exhibition of his work in this country to date. Therefore the aim of the day was to begin conversations about how the critical reception for Li’s work had changed and how Li could be situated within current dialogues about Modernism.

This was the question that Yu Wei opened with in his keynote paper ‘Art & Artefact’. How can/should we reconcile Li’s relationship with the object to ideas of conceptualism? Wei traced object-hood in Li’s work from the initial abstract calligraphic line, to a more discernible and later signature ‘cosmic point’. A point that moved from flat fields to folded books, from paper to cloth, to the panel reliefs that hung on the gallery wall space, activated like turning pages in a book and where the point itself became a tactile and participatory object that the viewer could move freely through the environments created. Wei identified Li’s participation in the ‘3+ 1’ exhibition at Signals Gallery in 1966 at the invitation of David Medalla and Paul Keeler as a decisive moment in Li’s career, enabling him to form, in Wei’s words, “an inseparable connection” between his own interest in interactivity and participation and the wider context of counter-cultural activity in London at that time. The three aspects of the Daoism that influenced this “visual philosopher”: simplicity, spontaneity and wu-wei had found a temporary home at least, in the mid-1960s artistic underground. If Li’s art can be aligned with conceptualism, Wei suggested it was far closer to the concept art of Fluxus, through the emphasis Li placed on toy-like interaction and multi-sensory participation.

The curatorial realities and challenges of staging such participation were explored by Hilary Floe in her presentation ‘POPA at MOMA: Pioneers of Part-Art’. For his contribution to this ‘Part-Art Show’ held in Oxford in the spring of 1971 Li created an immersive environment out of tissue paper, transparent sheets of plastic, Chinese paper birds and see-through ladders, to enable the audience participants to walk over tissue paper clouds and look up at the hanging constellations of red, gold, black and white discs, suspended like stars. Notoriously many of the art-works were destroyed or damaged on the opening night, leading to a withdrawal of the works from the exhibition by some of the artists. However Li made the decision not to withdraw, leaving his very fragile environment in situ for the duration of the show. Andrew Wilson, in his response to Floe’s paper, was “moved” by Li’s openness to the mayhem of this (over)participation. The rules of participation, framed by the artist and/or the institution but flouted by the good/bad participation of a group of drunken under-graduates were rules with which Li did not necessarily engage or apply to himself. Could it be said that Li had challenged this museological framing by permitting the work to be destroyed? This question intensifies when one considers that, at the time, Li was already beginning a decade-long project to make, with his own hands, the LYC museum in Cumbria.

The consideration of contemporary museological frameworks was discussed in the final discussion of the day, where BAM researchers Marlene Smith and susan pui san lok explored the modernist criticality of the work, mediated and unmediated, as experienced on research visits to Tate Modern to see two recent displays of Li’s work and Li Yuan Chia at the Richard Saltoun Gallery in 2016. One of BAM’s propositions has been that the socio-political and the biographical have not served us well in the search for the significance of the art itself, proposing a “dialogical formalism” as a method for getting back to the work itself. In this way, Li’s current inclusion in the display at Tate Modern’s Switch House was evaluated for its direct placement alongside works such as Medalla’s ‘Bubble Machine’ in comparison to the small solo display the previous year. My own interest in Li’s works and my decision to curate his work alongside that of Dom Sylvester Houédard and Kenelm Cox, in the exhibition Performing No Thingness, East Gallery, NUA, (2016) similarly proposed a “phenomenological formalism” with which to consider the object (lessness) in Li’s work and those of two of his close contemporaries.

Common to all these recent presentations of his work, however, is the curatorial and conservational reality that toy art can no longer be toyed with – it is strictly forbidden, or as Marlene Smith stated, “the museum forecloses all interaction with the work.” Nick Sawyer, a close friend of Li and former trustee of the LYC Foundation, drew attention to the 2015 retrospective of Li’s work at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum and the 2001 exhibition at Camden Arts Centre, where a room of replica ‘Cosmagnetic Multiples’ were installed, and the audience could place and replace the cosmic points continually through the day. Notably this room usually held the highest concentration of visitors. This led to study-group questions: Do we need a different museum for this kind of work? To what extent is the messiness of the original lost in any restaging? Is looking at the work enough of a compensatory strategy for not touching? To what extent was Li consciously subverting the very word ‘museum’ in the act of naming the LYC Museum? As Andrew Wilson concluded, “thinking about the LYC Museum is a different kind of thinking to that of thinking about the Tate as a museum […] Li was giving a frame to his own activity.”

Perhaps the most recurrent thread throughout the day was the expansive scope of this activity: Li’s own multi-disciplinary approach to his art. He rarely exhibited his own work at the LYC Museum, instead doing much of the manual labour of the construction itself: plumbing, brick-laying, roofing, rewiring etc. Is this “hard labour” (Wei) not also part of “the meta-catalogical revolution” (Wilson) with which Li engaged? As Guy Brett wrote in Iniva’s monograph of Li Yuan Chia, tell me what is not yet said (2001), in the making of the LYC Museum, Li taught himself: “Photographic colour printing, typesetting and lithographic printing, plumbing, wiring, wood-carving, gardening, wine-making, bee-keeping, musical composition, film-making, Spanish, French, German and Arabic.” A lifetime of actions all contained in the simple gesture of moving a small palm-sized magnetic point from one place to another.

Nicola Simpson is a curator and researcher based at Norwich University of the Arts and curator of Performing No Thingness DSH, Ken Cox and Li Yuan Chia, at East Gallery, NUA, 2016. Her interests are in Concrete Poetry and Kinetic Art, particularly the influence of Zen and Tantric Buddhisms and Taoisms on the Performance Art, Participation Art and Kinetic Theatre of the transnational artists of the 1960s & 1970s and the British counter-culture. Her doctoral thesis is right mind-minding: the transmission and practice of zen and vajrayana buddhist method practices in the poemobjects of DSH 1960-75 on the Benedictine monk and artist Dom Sylvester Houédard.

Endnotes: 1 Yu Wei ‘Art & Artefact’ in Viewpoint: A Retrospective of Li Yuan-chia, 2015, catalogue in 4 volumes produced by Taipei Fine Arts Museum. 2 Hilary Floe “Everything Was Getting Smashed”: Three Case Studies of Play and Participation 1965-1971,’ Tate Papers, no.22, Autumn 2014: http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/22/everything-was-getting-smashed-three-case-studies-of-play-and-participation-1965-71 3 Guy Brett, ‘Space-Life-Time’, tell me what is not yet said, 2001, published by Iniva (Institute of International Visual Arts) on the occasion of a major touring exhibition at Camden Arts Centre, London; Abbot Hall Art Gallery and Musuem, Kendal; and Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels.