The last Clothes, Cloth & Culture Group meeting focussed on the theme of ‘Cloth and Social Action’. Françoise Dupré spoke of her work during the 1980s in collaboration with the Brixton Art Gallery, in particular the Patchwork of Our Lives banners created with a group of Soweto women at the height of the anti-Apartheid campaigns in 1986. She also spoke about Women’s Work, an arts organisation that she co-founded. She recalled the annual banners that they made, drawing on earlier political banner making traditions, for example, those worked by the Socialist Movement and by the Suffragettes. This stitching, piecing and embroidering was of course happening around the time of Rozsika Parker’s Subversive Stitch and the subsequent show at the Cornerhouse and Whitworth Art Galleries. This was the era during which the barriers between craft and art began to be torn down and the domestic space was shown to be the political space that perhaps it always was, particularly for working class women. Dupré went on to discuss her current work concerned with cosmopolitanism, with the plasticity and the sociability of textile crafts, with the use of textiles as a ‘portal’, and with the crafting of space through collaborative participatory social practice, that binds the haptic to the making of socially meaningful art objects. She reminded us of Stuart Hall’s notion of ‘home’ as process; a concept that rests on ongoing engagement, i.e. something that needs to be ‘worked’.

The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. Rozsika Parker. Cover Image © I.B. Tauris

These points were brought to life by Victoria Khur, Ruth-Marie Tunkara, the QSA ‘Knees Up’ knitting and crochet club ladies and Derek (currently the only male member of the club). Through a ‘vox-pop’ style film, Khur and Tunkara relayed tales of newly formed relationships that cross generational, economic, racial and cultural divides, stories of the sharing of

knowledge and expertise, and accounts of the empowerment of the residents that

attend the club. A project of Quaker Social Action, situated in London’s,

Bethnal Green, ‘Knees Up’ uniquely promotes a belief in the possible by focusing on what is strong in communities, rather than what is wrong with communities. The title of their presentation, ‘Weaving a Community Tapestry’, neatly sums up

the common ground between the two presentations and the content of the discussions that followed. At a certain level, Dupré, Khur and Tunkara’s talks were underlined by this notion of possibility, which is aligned to the idea of unity through difference.

Earlier on that Thursday, I had visited PROGESS at the Foundling Museum, Brunswick Square, London. Set out over three floors, the exhibition marks the 250th anniversary of William Hogarth’s death by showcasing the responses of four contemporary artists – Yinka Shonibare MBE, Grayson Perry, David Hockney and Jessie Brennan – to his infamous series of etchings A Rake’s Progress, (1735). Grayson Perry’s the Vanity of Small Differences occupies the basement.

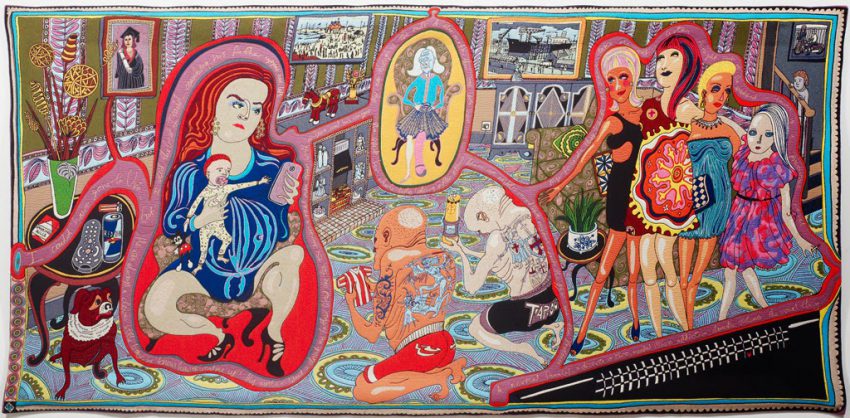

Grayson Perry, The Vanity of Small Differences, The Adoration of the Cage Fighters, 2012. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery, London © The artist

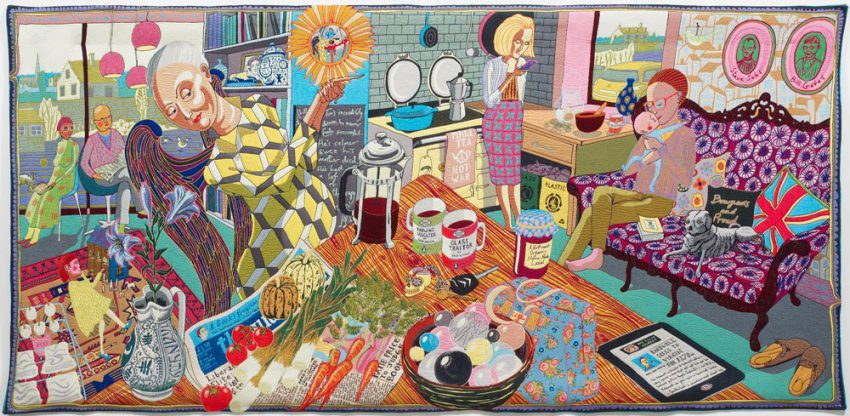

Perry’s the Vanity of Small Differences consists of six tapestries charting the progress of Tim Rakewell. These densely woven and richly coloured tapestries provide Perry with a means through which to explore issues around class and taste as the exhibition catalogue tells us. But, in my view, these intricate hangings also speak about today’s rapidly changing urban landscapes, or ‘social fabric’, to reference a previous Iniva project. Rakewell’s progress tells the story of not only the demise of a man but also the breakdown of communities that we all too often witness in this contemporary moment. Today’s fast-paced social upheaval could be said to parallel that of the 1980’s noted above: the unstable economic climate, the gentrification of former working class areas coupled with a dearth of affordable housing, the rise of far right political movements, the growing fragmentation of society. Biblical references, compositional strategies reminiscent of religious paintings and narrative structures based on Hogarth’s original Rake collide with recognisable symbols of wealth and lack of wealth in Perry’s series: a cafetiére, an allotment, a young ‘baby mother’, a smart phone, a copy of Hellomagazine. The viewer is taken through the various stages of Rakewell’s journey from his working class roots to his rise to the upper classes. The last tapestry #Lamentationdepicts our protagonist’s violent passing at the wheels of his Ferrari. His body, pulled from the wreckage and surrounded by capitalist markers of success, lies motionless at the centre of the scene. The whole is tweeted by onlookers positioned in the background of the piece, hence the Twitter hashtag in the title. Might this final act represent the ultimate rending of a community tapestry?

Grayson Perry, The Vanity of Small Differences, The Annunciation of the Virgin Deal, 2012. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery, London © The artist

Progress: William

Hogarth, Yinka Shonibare MBE, Grayson Perry, David Hockney, Jessie Brennan

The Foundling Museum

6th June –7th September 2014

By Christine Checinska