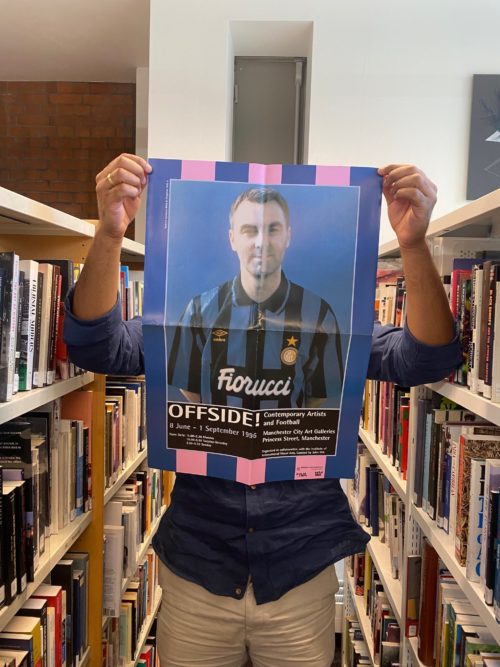

Devaan Deese with Offside Exhibition Poster in Stuart Hall Library

Devaan Feese explores questions of nationhood and representation through researching Offside! Contemporary Artists & Football exhibition in iniva’s archive and utilising Stuart Hall Library collections.

There are many ways in which various forms of material can represent a nation’s ideals and aspirations. Colours, patterns, symbols and emblems transform pieces of cloth into tangible identity. We see this abundantly in international football tournaments; the team shirts, badges, flags. As we see the faces of nation changing rapidly through the representation of national teams, to what extent does this symbolism reflect this?

Sporting events can bring a nation together. Who can deny the national morale boost England progressing through an international football tournament brings? The hopes of a nation are realised or destroyed, depending on which net the ball hits the back of. As explored in Offside! Contemporary Artists and Football, a stadium becomes the stage upon which national aspirations are projected, and the players become heroes and fantastical. But it can also reveal national angst.

The national stadium at Wembley hosted the Euro 2020 final: England v Italy. With a crowd 67,000 strong and a global audience of 328 million, Marcus Rashford, Jadon Sancho, and Bukayo Saka, all sporting the England flag on their shirts, failed to score during the penalty shoot-out. Immediately, social media was inundated with racist posts. In response, Rashford apologised for the missed goal but refused to apologise for who he was and where he came from. Sancho stated that “as a society, we need to do better and hold these people accountable”, while Saka “knew instantly the kind of hate” he was going to receive.

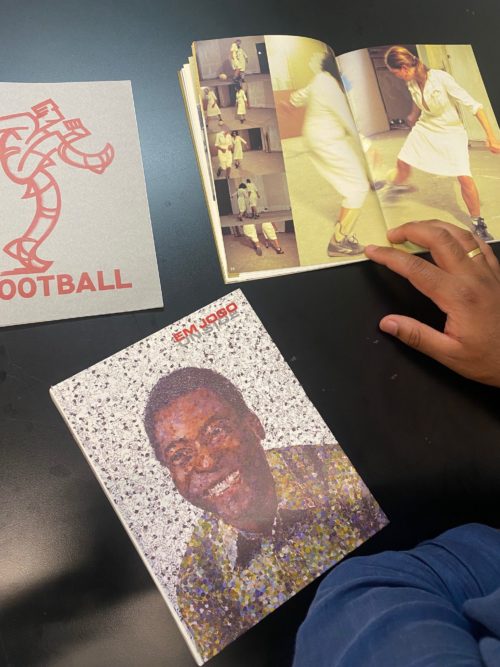

Devaan Feese with books on football from Stuart Hall Library

The English national team (as across all the English leagues) now has more black players than ever before. Whilst this signals the changing face of English football, Bilkes Malik suggests this does not reflect the national psyche. The need to self-identify often requires opposition to an ‘other’, and is prevalent throughout football. Even at club level, opposing fans are kept securely away from each other in the stands to avoid violence. On an international level, England ‘unite’ under the flag while there is a clear ‘other’ (the opposition). However, as seen in Euro 2020, match results reveal a thin line between a (potential) home-grown hero and an ‘other’. Internationally, black football players take centre stage to represent a nation but domestically remain peripheralized. Same context, different spheres. How does one navigate being ‘us’ and ‘them’?

On 25th October 2000, a conversation took place between Stuart Hall and Sarat Maharaj at an iniva event (later published as Annotations 6: Modernity and Difference, 2001). They discussed the translation of experience from one culture to another. Stuart Hall commented that ‘mistranslation is inevitable as there can never be a perfect rendering of translation from one language or space to another. Could this also be the case for identity? Through international football tournaments, we see what Stuart Hall referred to as the “margins coming into representation”.

Can Nation ever fully ‘translate’/understand marginalised identities?

As St George’s Crosses flood stadiums, does a symbol associated with crusades against “Islamic occupation” really unite an increasingly diverse nation? As England grows increasingly secular and multifaith (uncomfortably simultaneously), does this Christian imagery still embody national identity for the entire nation?

How does this translate?

Speaking of the exhibition Veil (curated by Jananne Al-Ani, David A. Bailey, Zinab Sidera and Gilane Tawados), Sidera refers to the complexities of the Western gaze upon women wearing veils. She intended the art presented to be viewed as ‘transgression’. Interpretations of Africa celebrated Africa’s identity and culture through artwork that resulted in football kit design for 10 PUMA-sponsored African national teams. These projections of national identity by those upon which identity was/has been given feel radical and transgressive.

Second Skins, an event held by iniva in 2009, explored the issues of identity and cultural heritage, as well as its personal and collective associations, as expressed through cloth (“Cloth speaks”). The question is raised: “What roles does cloth play in the re-fashioning of identities in geographical and symbolic border crossing?”

Given the chance to reimagine ‘us’, what symbols would we choose to showboat?

Biography

Devaan Feese is currently studying MA in Museum Cultures at Birkbeck, University of London and was iniva’s Programme Assistant within Stuart Hall Library as part of his work placement. He has an interest in archives and artistic and literary challenges to perceptions.