This month, Lyn highlights some of the feeling states featured in the recently published A To Z of Emotions, exploring concepts such as emotional fragility, ego ideal and false self.

We are probably all aware of the ways in which any government or society can implicitly or openly suggest that private distress, alienation and mental health issues are self-generated and therefore the responsibility of the individual. However, the personal, the social and the political are always in dynamic relation with each other. Questioning what we mean by terms such as ‘sane’ or ‘healthy’ often means critiquing how we, as a society, label, treat and even institutionalise those who are assigned the opposite labels. Deepening and broadening our understanding of our emotional life may mean facing up to the fact that we all have pockets of dysfunction, often a result of difficult life experiences which may have nothing to do with ‘self-generated’ distress. The child who is bullied badly in early years by an older sibling or a peer, for example, may turn out to have a very fragile sense of self.

Image illustrating FRAGILE © 2014 Dia Batal Fragile/ Fearful, Ink on paper, Digital composition

Dia Batal has illustrated the word ‘fragile’ for our A to Z of Emotions by creating a graphic image of a lower-case letter ‘f’ that looks as if it is trying to ‘hide’ behind a transparent curtain. The child who is bullied or made to feel very self-conscious because of how he or she looks, acts or just ‘is’ may turn into a young person or adult who is emotionally fragile and has a damaged or distorted inner picture of themselves. This can impair confidence and lead to wish not only to hide from others but also from looking too closely at ourselves.

We all have a basic need to respect and like ourselves and to be seen by others as ‘good people’. Whether we are aware of it or not, we have an inner picture of the kind of person we’d like to be and how we wish to be viewed by those around us. In psychological terms, this is called the ‘ego ideal’, that is, the idealised image of ourselves that we carry in mind. If we have had more than our fair share of harsh treatment or criticism when younger, we may not be able to hold onto an ego ideal. However, such early damage doesn’t have to be permanent. We now know that we can influence our thinking about ourselves by challenging negative self-talk. As well, mutually supportive and emotionally honest relationships and friendships can re-configure our early patterns of relating and go a long way towards repairing our sense of worth.

Perhaps our early years were very different. Maybe our experiences have been primarily self-affirming and our ‘ego ideal’ seems intact. However, sometimes things happen that make us see ourselves from an unexpected angle and we discover that we aren’t ‘the perfect self’ we’d like to imagine we are. It’s as if a hidden, more vulnerable or ‘bad’ part of ourselves is exposed. Being put in touch with our less likeable parts can come as a shock, especially if we’ve been dishonest with ourselves about some of our more uncomfortable feelings such as jealousy, envy and even hatred.

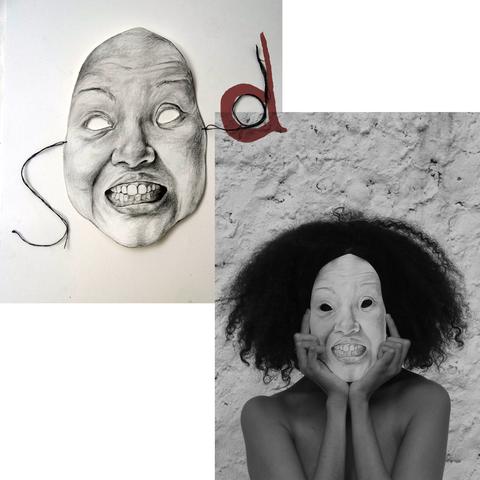

Image illustrating DISHONEST © 2014 Phoebe Boswell Dishonest, Pencil on Paper

Phoebe Boswell’s drawing of a woman holding a mask in front of her face reminds us of how we can all show the world a ‘false self’ by trying to be someone we aren’t. Some of us develop a false self in infancy and childhood through picking up very early on that our mother or primary carer needs us to be a certain way. We learn to ‘perform’ and bury our authentic self as we sense that our emotional and physical survival is dependent on pleasing our carers. For others, an inauthentic self takes hold as we grow older and make more conscious decisions about what we want to show to the world regarding who we are. In highlighting the word ‘dishonest’, Phoebe Boswell has chosen to illustrate a woman of colour holding up a lighter skinned mask which takes the exploration of emotional dishonesty in an important direction – if we cannot accept our heritage which is literally ’embodied’, if we try to fundamentally alter how we look or symbolically deny our heritage in some way, we are being dishonest about who we are and what our place in the world is.

Born in Kenya to a fourth generation British Kenyan father and Kikuyu mother, Phoebe grew up as an expatriate in the Middle East and now lives and works in London. Drawing is at the heart of her practice, which encompasses hand-drawn animation, projection, and installation to form multi-layered narrative languages through which to tell complex contemporary global stories. These stories cannot always be adequately told in a single image or a single screen film. Propelled by the contradictory nature of her own fragmented upbringing, her practice is imbued with a personal yearning to explore notions of what it means to belong.

Image illustrating LOSS © 2014 Dia Batal Loss, Detail from ‘Mourning Hall’ Commemorating Syrians killed by the Syrian Regime during the uprising 2011-2012.

Some of us, however, still carry undigested or yet to be processed feelings of dislocation relating to the loss of our homeland which may have come about due to earlier generations being forced to migrate due to lack of employment, political unrest or war. Returning to artist Dia Batal, she has created a poignant illustration for the letter ‘L’ depicting Arabic writing recording the names of people killed in the 2011-212 Syrian uprising.

Dia was born in Beirut in 1978 and is currently based in London. Dia’s multidisciplinary work is context-specific and often enables audiences to engage with it. She is interested in the way design can impact on people’s lives within public and private spaces and how it can reflect social, cultural, and political concerns. A powerful example of this is her project entitled ‘Mourning Hall’ in which Dia responds to the lack of mourning and burial spaces in Syria during the 2011-12 conflict. Each of the hand painted tiles featured in the project now holds a name written in Arabic calligraphy of a woman, man, or child who was killed during the conflict lending an identity and ‘space’ denied to the individuals and families of those killed.

Just as Dia has curated an external space to acknowledge a significant and far reaching loss which came about because of civil war, we need to create an internal, reflective space in which we can explore our experiences of emotional loss, dislocation and disturbances to our sense of self. Our inner strength will always be tested. We’ll never reach a point when our emotional muscle is as strong as we might want it to be. Instead of hiding from true feelings or staying stuck in a painful place or avoiding mourning our losses, we can learn what we need to do to recover and move on.

Written by Jenny Starr