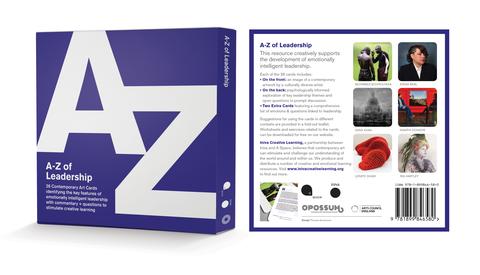

We are delighted to announce the upcoming launch of our new publication the A to Z of Leadership (available now), a new set of contemporary art cards which explores themes relating to emotionally intelligent leadership. Whether we are aiming to be a role model at home or in our community or hold a more formal leadership position, the themes covered in the A to Z of Leadership are relevant to everyone. This month, Lyn French (A Space Director) introduces key themes around leadership using images from the new set.

Most organised groups have a leader or someone who assumes this role either by tacit or explicit agreement. Depending on the context, some leaders engage in training to prepare them to take up their position while others draw primarily from their own resources. Either way, few pause to think deeply about our earliest relationship with authority which takes place within the family setting and the imprint this leaves behind. We don’t generally assign a leadership label to parents but this is, in fact, what they are. They organise the family group and have the authority invested in their role to set the moral tone. All of the descriptions assigned by business manuals to leadership styles can be applied to parents too. Some parents are, for example, more democratic than autocratic or value a participative approach over ‘command and control’ and vice versa. Others are charismatic, inspiring respect by their innovative and personal approach.

The way in which we were parented will reflect how our parents adhered to, or reacted against their parenting. In turn, our relationship with authority is likely to be rooted in our childhood experience of those in positions of authority including our parents and, in some instances, older siblings and grandparents as well as teachers and head teachers. Perhaps we’ve reacted to what we felt was a dominant or overbearing leadership style by valuing the opposite – non-hierarchical leadership. Or maybe we have primarily experienced those in authority as being without firm enough boundaries and we’ve responded by becoming somewhat over-dependent on structures. These broad-brush descriptions show how we are all shaped by the past whether we are aware of it or not.

Our new set of emotional learning cards, the A to Z of Leadership, explores the conscious and unconscious impact of family, culture, society and our individual psychological makeup on how we conceptualise the role of the leader. We all have degrees of authority invested in us whether it is in the context of our social or family groups or in the professional sphere. Additionally, whatever our current place or position in life, there are bound to be those who hold authority over us.

Idris Khan – St Paul’s (2012)

On first glance, Idris Khan’s drawing of St Paul’s Cathedral may seem to have little to do with leadership. But if we take time to think about it, we can probably see that the artist may be inviting us to reflect on the multiple meanings we project onto historic institutions and their emotional resonance. A leader based in a landmark building may, for example, unthinkingly be assigned more importance or authority than one working in a non-descript office or from a virtual desk. The language of architecture is a potent one and can be read on various levels. Monumental buildings often convey a sense power and, along with this, an unquestioning belief in ‘how things have always been done’. Whether we are taking a lead role in our family or social group or we are head of a large organisation, our internal relationship with our own authority will determine the degree to which we command respect regardless of the kind of office we physically occupy. If we are first-born, we might feel that leadership comes naturally to us and adjust easily to taking on a responsible role. However, if we are, second or third born, we could unconsciously believe we are usurping the role of an older sibling and this could affect how confident we feel exercising authority.

Nina Mangalanayagam ‘Easter’ (2008)

Nina Mangalanayagam’s photograph entitled ‘Easter’ from the series Homeland navigates similar terrain rooted in family experiences. In the domestic scene depicted, the father looks on as his daughter decorates eggs- a Western tradition associated with a Christian festival. The father is clearly from another culture. As his expression is somewhat stern, he may well be wondering how Easter fits in with his belief system or background and could even feel a degree of concern about the distance that might be developing between him and his adult daughter. The daughter, too, may experience herself as caught between two or more cultures, wanting to fit in but equally wishing to honour her parents’ heritage. Leaders will inevitably face this kind of complexity when they discover that their own approach to a role veers away from their ‘professional parents’, that is, from those who have trained or taught them. It is common to begin by idealising our elders. When we evolve new ways of thinking, we can feel a range of uncomfortable emotions. Along with guilt at abandoning the previous generation’s traditions or ‘norms’, we might also be anxious, wondering if we can trust that our way will indeed be better. At the same time, we may also be in touch with our gratitude for the support we have had in the past from those who have gone before us.

Razwan Ul-Haq ‘Calligraphy Pirate’ (2007)

We always learn from previous leaders even if we move on to new approaches or different ways of thinking. Razwan Ul-Haq’s ink drawing blends the ancient practice of Arabic calligraphy with contemporary subject matter. Reflecting on his practice, we might be reminded that in antiquity, pupils studying Arabic or Islamic calligraphy copied their teacher’s style repeatedly until they had perfected their art. We gain from what is handed down to us through training and working with those who are our elders or seniors. Equally, those who are younger than us or work for us follow our lead. We all learn more from observing others than from what we are told or instructed to do. Qualities such as thoughtfulness and generosity rely on our willingness to make mental time and space to support those who follow us or are struggling in some way.

Growing into the role of a leader whether at home or in a professional context is a process which is shaped by internal and external influences. How we have managed our early relationship with authority plays a key role.

The A to Z of Leadership is unique in the depth of breadth of the themes it covers. Being a compassionate, creative, collaborative and transformative leader in our own lives depends on building our insight into our past and effectively managing the emotional and psychological demands placed on us by our present circumstances.

Written by Jenny Starr