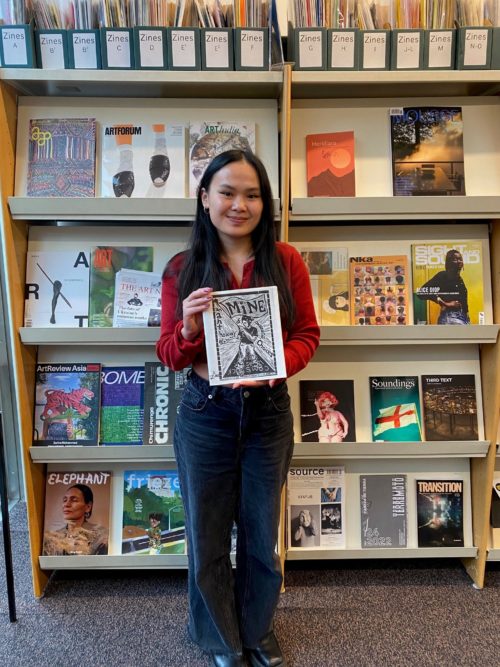

Volunteer Hannah Dunsmore in Stuart Hall Library with zine Mine: An Anthology of Women’s Choices by Meredith Stern, 2023

Our recent volunteer Hannah Dunsmore reflects on the zine Mine: An Anthology of Women’s Choices by Meredith Stern, found in the Stuart Hall Library collection.

TW: The zine highlights the topic of abortion rights that may trigger uncomfortable feelings or traumatic experiences

For me, last year, the word choice became synonymous with an ideological shift in the United States which culminated in the removal of a person’s rights over their own womb. The year 2023 marks fifty years since Roe v. Wade, the court case that legalised abortion in the United States, and six months since that constitutional right was revoked.

During my time at Stuart Hall Library, I have been stock-checking the library’s collection of zines from A to Z. Nestled within the box marked M, I discovered the zine Mine: An Anthology of Women’s Choices by Meredith Stern. Published in 2002, Mine is a collection of stories, collected via an open call, by women sharing their personal experiences with abortion procedures (medical and surgical, menstrual extraction, herbal remedies, etc.). The voices vary from women who are stoically pro-choice and those who share more mixed feelings. Some choose to share their name, and some choose to remain anonymous.

The DIY nature of zines and the collective ethos behind the creation and distribution of this type of publication fosters a unique relationship between the writer and their readers. As a reader, you get the impression that Meredith did not edit (at least heavily) the stories she chose to publish. There are grammatical errors, unfinished sentences and swear words are not censored. Each writer has a distinctive narrative style, complemented by different typewritten fonts. The zine is a collaborative journal with multiple entrants and reading each entry feels like a personal encounter with each correspondent.

The cover of the zine features a linocut print by Meredith of a woman holding a flag with the word Mine. The dot above the “i” is replaced by a uterus symbol, a visual signal to individuals with a womb that any decisions over this organ (in their own body) are theirs to make. This message rings truer, from a legal standpoint, 21 years ago than today. Currently, 13 US states have banned abortion and a further 11 have placed a gestational limit on the procedure and/or have bans indefinitely blocked by judges/appeals courts (New York Times, 2023). Due to this, returning to the aims of the zine to de-stigmatise abortion by amplifying the voices of those who choose to go through with the procedure is even more important today.

At the time of publishing in 2002, the anthology served as a reminder that although Roe v. Wade gave people the right to abortion, it did not protect people’s access to abortion, with references to many US states’ requirements such as 24-hour waiting periods and parental consent. Across states and across these stories, writers faced similar barriers at every stage. Some writers recount the arduous process of locating trustworthy advice centres and clinics, for example, having to trawl through the Yellow Pages after being handed a lone phone number scribbled on a scrap of paper or encountering anti-choice organisations fronting as abortion providers. Other writers recall enduring traumatic experiences once at the clinic including having to wade through crowds of protesters to be greeted by judgemental, condescending staff inside, sat down and being forced to consume abortion alternative material.

Through her selection of anecdotes, Meredith encourages a nuanced dialogue on the varied impacts an abortion can have on an individual. She does this by including women who see abortion as an empowering experience and a journey of understanding their body but also, those who face internal conflict over being pro-choice but feel unable to grieve their loss and are seeking a system for help.

The overarching message, however, epitomised in Meredith’s method of collecting the stories via submissions, is the need for people to openly share their experiences. Many writers express how cathartic the process of recording their stories on paper is and some encourage others to do so also, by asking for readers’ responses to be sent to their P.O. boxes. With the inclusion of reprinted material on the subject from other zines, Meredith affirms that this topic should be discussed in channels beyond her publication. By providing a space for her writers to speak candidly, she validates all opinions within the pro-choice spectrum.

I imagine reading this zine now is a very different experience from reading it when it first came out. The same words which symbolised a progression in the reproductive rights of pregnant people in the US in 2002 are now a stark reminder of a regression. Reflecting on her second abortion and a bad experience with herbal remedies, a writer from Oregon states: “This was a turning point in my life, I was sick and wretched, and I realized for the first time how lucky we are to have abortion and other surgeries available to us.” While abortion in Oregon is still legal today, the term “us” can no longer be applied collectively to all pregnant people in the US, or even, to all her fellow zine contributors.

On page 6 of the zine a writer from Louisiana likens her experience with abortion to an ‘illegal exchange’, as she was directed by a clinic to “bring all the cash” and “come alone”. Abortion in this state is now banned with almost no exceptions. She notes that the “grand total of [her] misfortune was $400.” A costly sum then for a basic healthcare need and will no doubt cost exponentially more now (it is legal to travel to another state to get the procedure).

In the introduction of the zine, Meredith writes “Still, there are numerous friends and acquaintances who have had abortions but feel uncomfortable writing about their experiences.” This is still the case today but sharing your story may have legal implications if you can’t afford to travel out of state for the procedure. The overturning of Roe v. Wade interrupted my (admittedly naïve) presumption that once granted, the freedom to make the final decision over your own womb could not be taken away.

Mine thoughtfully unpacks the importance of having a choice in all matters relating to taking ownership of your own body. The publication’s composition can be compared to a stack of letters, written with such bleak honesty, you may forget you are not the only intended addressee. In 2004, Meredith released a second zine of stories titled Mine: An Anthology of Reproductive Rights. I hope she releases another collection in the next couple of years as reducing the shame around abortion is even more crucial now.

References

New York Times. (2023) Tracking the States Where Abortion Is Now Banned. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade.html

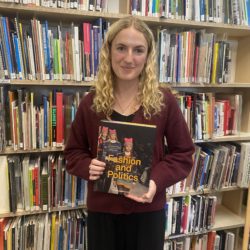

Biography

Hannah Dunsmore is the Project Manager at Self Publish, Be Happy and Social Media Officer at Mostyn Gallery. She has completed an MA in Documentary Photography and Photojournalism at the University of Westminster. She is currently working on publishing a zine titled Atonal with Molly Stock-Duerdoth and has been volunteering at Stuart Hall Library since September 2022.