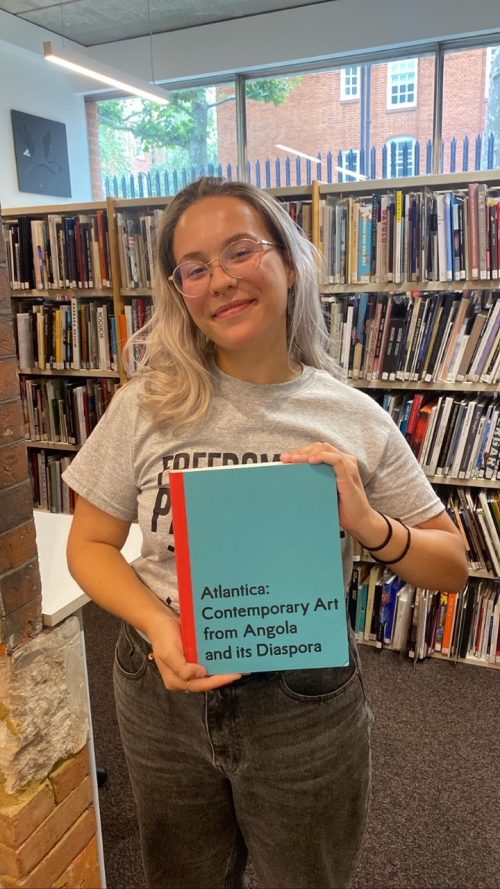

Volunteer ines silva holding book “Atlantica: Contemporary Art from Angola and its Diaspora” in Stuart Hall Library, July 2022

Stuart Hall Library volunteer ines silva reflects on Angolan artist Délio Jasse’s careful reframing of family photographs from Portugal’s colonial occupation of Mozambique.

I had never heard of Atlantica: Contemporary Art from Angola and its Diaspora (Dantas, 2020) until I found the book in the Stuart Hall Library. This wouldn’t have been so strange had I not lived in Lisbon for 21 years, just 5 kilometres away from HANGAR, the research centre that published it. Inside this book I met Délio Jasse’s work for the first time, his series The Lost Chapter Nampula – 1963 that has still been etched into my mind.

The “Black Atlantic”, understood in the stead of Paul Gilroy (1993), is a counterculture of modernity imagined and practiced as a refusal and denunciation of whiteness, imperial colonialism, and the centres as the sole agents of History. In this blog post, I consider the work of Délio Jasse through the notion of a Creole Atlantic – a metonymic framework that avoids centring the coloniser’s narratives. I also grapple with the question of temporality. How are contemporary artists engaging with the ongoing disaster of transatlantic slavery, colonialism, and coloniality? If we take Trouillot’s challenge to face pastness as a position (2015), how are these artists refusing the Portuguese state’s official aphasiac chronology, which disavows colonialism and racism as psychological, a-historical problems of individual moral deficit? I focus on artistic reactions because of their ability to practice radical epistemic disobedience. Where Western rationality is premised on a set of colonial binaries (past/present, traditional/modern, masculine/feminine, here/there, we/they), art can deploy various aesthetic sensibilities that not only challenge but ridicule this parochial worldview. Artistic production is a type of knowledge more attuned to the intimate stories that counter the violence of abstraction.

Let us look at The Lost Chapter Nampula – 1963. In a flea market, Jasse found a family photo album with pictures taken in Nampula, Mozambique. Remember the mass exodus of white settlers when the anti-colonial war erupted in the 1960s. Remember these settlers left in a hurry, taking as much as they could, destroying everything they couldn’t take. This photo album is evidence of a crime, but how could that be made evident? By using a liquid emulsion process to layer official stamps from the colonial government over these seemingly innocent family pictures, the artist radically questions the frame, the imperial shutter, and discourses that produce them. A photograph’s ostensible objectivity conceals the choices being made around the shutter. What will be in and out of the frame? Who is taking the picture and for what purpose? Where will the picture be stored and who will have access to it? The saturated official stamps juxtaposed over these black and white intimate scenes work as a double provocation. They question the State (remember Salazar’s dogma we do not discuss the fatherland[1]) but they also remind us that the State is not just an abstraction. In this way, Jasse’s work refuses “white moves to innocence” that wish to forget, erase, burn, discard proof of their investment in colonial exploitation.

Jasse offers us imaginative ways of sitting in a room with history (Brand, 2002). His works are powerful pieces that continue to tell the story of colonialism’s stamp on the present, creolising the grand narratives of “Atlantic discovery”. By engaging creatively with photographs, frames and the context in which they were retrieved, Jasse situates us in the wake (Sharpe, 2016): the moment and place where we recognise colonialism as an ongoing trauma that we must mourn, but also from where we can imagine otherwise. This is crucial not just for Black Portuguese people negotiating their sense of belonging and consciousness within/against a profoundly racist, negligent state, but also to white Portuguese – like myself – who must decide whether they will be complacent or engaged witnesses in postcolonial times.

[1] Antonio de Oliveira Salazar led Portugal’s fascist colonialist Estado Novo [New State] dictatorship, which lasted from 1933 to 1974. In this speech he famously stated “we do not question the fatherland nor its history”.

Biography

ines silva is currently completing her MA in Postcolonial Culture & Global Policy at Goldsmiths, University of London. She has been volunteering at the Stuart Hall Library since March 2022, where she learned that art isn’t as intimidating as it seemed. For the future? The chance to keep thinking and doing with others until we believe there are many alternatives.

References

Azoulay, A. (2019). Potential History. Unlearning Imperialism. London: Verso Books.

Brand, D. (2002). A Map to the Door of No Return. Vintage Canada.

Dantas, N. (2020). A sliver, os a sliver, of a sliver. Lisboa: Hangar. [673 ATL]

Gilroy, P. (1993). Black Atlantic. Modernity and Double Consciousness. London: Verso Books. [ESS GIL]

Sharpe, C. (2016). In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Duke University Press. [ESS SHA]

Trouillot, M.-R. (2015). Silencing the Past. Power and the Production of History. Beacon Press.